Josef Sudek photos (44 photos)

Разрешение картинок от 248x500px до 3072x2304px

Josef Sudek was born on March 17, 1896 in the city of Kolin in Bohemia in what is now the Czech Republic. At the age of 14 he came to Prague, trained as a bookbinder, and worked for some time in the small town of Nymburk, 45 kilometers from Prague. His first experiments with a camera date back to this time. It cannot be said that photography immediately captivated the young man; at that time he was more interested in music than anything else in the world. In 1914, World War I began and a year later Joseph was drafted into the army. Then there were military everyday life on the Italian front, a seemingly not very dangerous wound in the right arm and terrible gangrene, which ultimately led to its amputation.

The young man spent three years in a veterans' hospital. At this time, he resumed his studies in photography: “You can press the shutter with one hand,” he explained his choice later. At first, he didn’t think of it as a way to make a living, he just needed something to do that would help him take his mind off the disappointing reality. And what can help better than getting involved in art? Later he drew and even tried his hand at painting, but at that time photography seemed to him the only type of creative activity available to him. It seems that it was creativity that helped him resist the physical, and even more moral, pain that accompanied him all his life. To give the reader a clear idea of how keenly Joseph Sudek felt his “flawedness,” I will cite his memories of a trip to Italy in 1926, almost 10 years after his injury:

“When the musicians of the Czech Philharmonic invited me: “Josef, come with us, we are going to Italy to give several concerts,” I said to myself: “Idiot, you were here in the Imperial Army, but did not see the beauty of this beautiful country.” And I went with them on this unusual excursion. In Milan we were received very warmly, and then we drove on until we arrived at that place (hereinafter it is emphasized by me - A.V.). I ran away from the concert; it was dark, I was lost, but I had to find him. I eventually found this place in the fields covered with morning fog, quite far from the city. But my hand was not there - only the poor farmhouse stood as before. They brought me into it after being wounded in my right arm. They were never able to fix me; for many years I bounced from hospital to hospital, and was forced to give up my profession as a bookbinder.

The guys from the Philharmonic were looking for me, they even called the police, but - I don’t know why - I couldn’t bring myself to leave. Only two months later I returned to Prague. They didn’t reproach me, but since that time I haven’t gone anywhere and never will. What should I look for there if what I need is still impossible to find?”

In 1920, Josef Sudek left the hospital and immediately began looking for a new job. He was offered a position in the office, but he refused. He was a little more inclined to think about opening a trading store, but quickly realized that this was not for him. In the end, the young man decided to earn extra money using his hobby - and his entire future life showed that this was the right decision.

From 1922 to 1924, Sudek studied at the State Printing School, whose photographic department was headed by the famous photographer Professor Karel Nowak. Most of Sudek’s classmates planned to work in a photo studio after graduation, so the main attention was paid to photographic portraiture, lighting, background selection, selection of accessories and many other intricacies necessary for a commercial photographer.

In the 1920s, Sudek had two favorite subjects: first his disabled friends from the veterans' hospital, and later the reconstruction of St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague. From time to time he went to his hometown of Kolin and photographed the parks. In 1921, Sudek joined the Czech Amateur Photography Club, where he met and became friends with Jaromir Funke, who at that time was just beginning his path to fame. Both of them – like many other Czech photographers of the time, including the legendary František Drtikol – were proponents of pictorial or “pictorial” photography. The American photographer of Czech origin, Dragomir Ruzicka, who came to Prague in 1921, had a great influence on the young people. Now this name is almost forgotten, but in the 1920s Ruzicka was a famous photographer, one of the founders of the American Society of Pictorialist Photographers.

However, their views on photography soon changed - from supporters of pictorial photography, Sudek and Funke turned into its ardent opponents, adherents of the so-called “pure” or realistic photography. Friends were expelled from the “Amateur Photography Club” and in 1924 they founded the “Czech Photographic Society”, the main goal of which was the struggle for the liberation of photographic art from the imitation of painting.

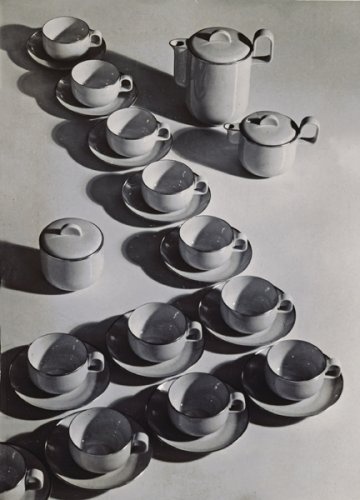

From 1927 to 1936 he worked for the Druzstevni Prace Publishing House, specializing in reportage, portraits and advertising. Gradually, passing through all the avant-garde movements of the time, the young photographer began to develop

howl own style. In 1928, a set of original (printed by the author) photographs of Sudek was published in a circulation of about one hundred copies - try to imagine how much such a set could cost today! In 1933, his first personal exhibition took place, and in the same year he took part in the International Exhibition of Social Photography.

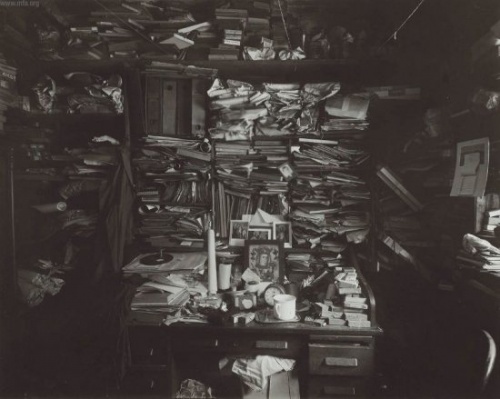

In 1927, Sudek purchased a small wooden photo studio with a small garden, where he lived and worked for more than 30 years. The history of the studio is as unusual as the life of its owner. It was built at the end of the 19th – beginning of the 20th centuries in the courtyard of one of the houses in the Mala Strana region. The location of the studio was extremely unfavorable, which the previous owner did not like at all, but was quite suitable for the new one. And he proved that “it’s not the place that makes the person, but the person the place” - in a couple of decades, Sudek’s atelier will become one of the main attractions of the city. After the death of the photographer, admirers of his talent tried to restore the building and set up a house-museum in it, but could not find the money. In the mid-1980s, the studio burned down, but was restored in 2000.

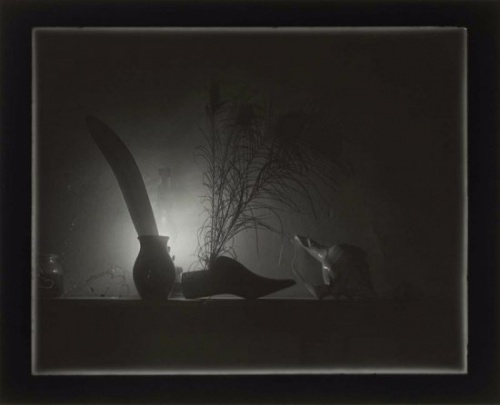

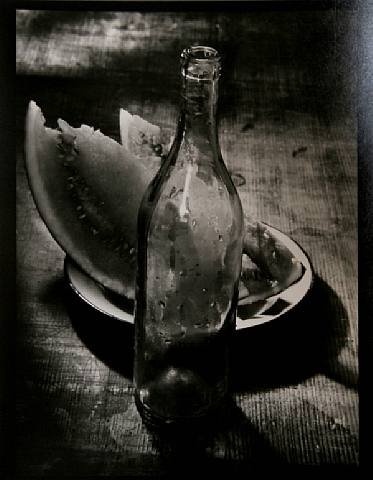

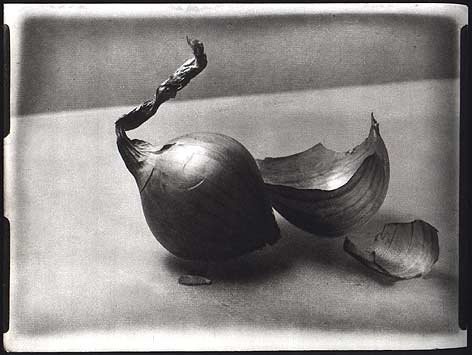

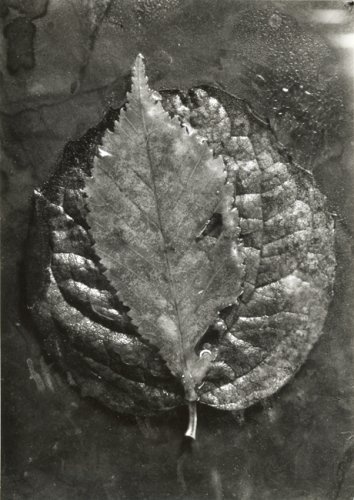

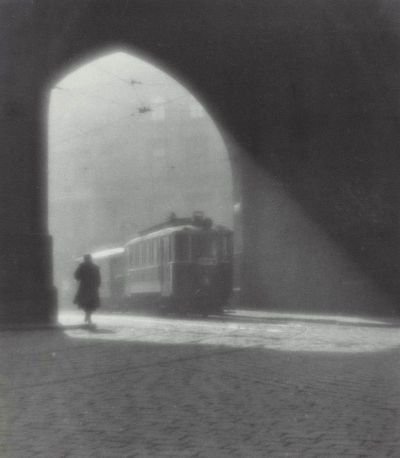

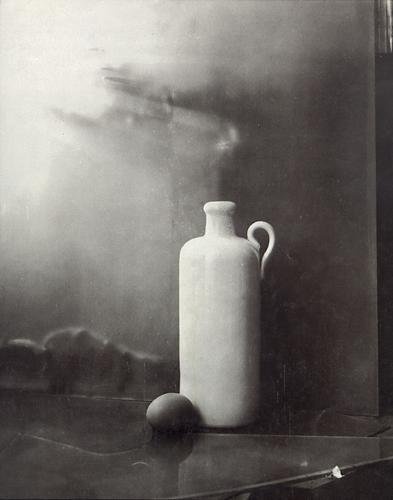

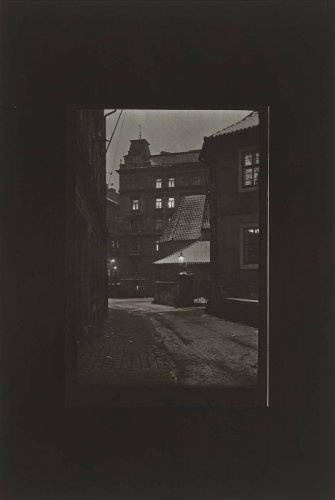

However, let's return to pre-war Prague. By the mid-1930s, Sudek had established a reputation not only as the leading photographer of the Czech Republic, but also as the most talented photographer who captured the beauty of its capital. His favorite time for photographic expeditions around his hometown was the early evening twilight, when there are not many people on the streets, and the statues and buildings seem to come to life - or at least so it seemed to him. “I love watching the life of objects,” he once said in an interview, “They come to life when the children go to bed. I like to tell stories about the lives of inanimate objects."

Soon the Second World War stood in the way between the photographer and his beloved city. In March 1939, Prague was occupied by Nazi troops and there was no question of going out into the street with a camera - as if, after his hand, he had lost his legs! But he still has his studio, and his amazing gift as an artist has not gone away. And for a long time the workshop became for Josef Sudek not only the workshop and home itself, but also the subject of photography. Soon new series of photographs appeared that were not inferior to the previous works of the master, and in some places even surpassed them. Perhaps the most famous of the projects created by Sudek is the series of photographs “My Studio Window”. A magical world, even two worlds separated (or maybe connected) by an old frame with not very transparent glass. One of them - kind and beautiful, sad and romantic - belonged to the artist, the second - to the rest of the world: good or evil, friendly or hostile. Work on the series took 14 years: he did not leave it even after the war, although he again began to go out, photograph Prague or landscape views.

Immediately after the war, Sudek advertised in a newspaper looking for a laboratory assistant. A young woman who had just been liberated from a concentration camp, whose name was Sonya Bullati, responded to him. For just over a year, she carried the photographer’s camera, assisted him with printing, and eagerly listened to his “chatter.” She soon emigrated to America, but the correspondence between teacher and student (my “uch-mouch,” as he affectionately called her) did not stop until the photographer’s death. Sonya left very interesting memories of Sudek.

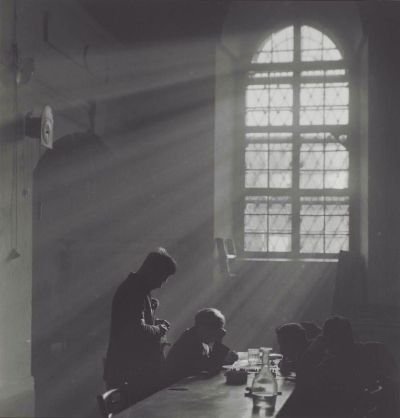

“I remember it was in some kind of Romanesque-style hall, deep under the spire of the cathedral,” recalled Sonya Bullati, “It was dark like in the catacombs, the light came only from a small window located below street level in the massive medieval walls. We set up a tripod and camera, then sat on the floor and talked. Suddenly Sudek jumped to his feet - a beam of light pierced the darkness. We both began waving our clothes and raising mountains of dust in order to, as Sudek put it, “see the light.” We, of course, did not come to this place by chance; he knew that the sun’s rays hit here two or three times a year and was waiting for this moment.”

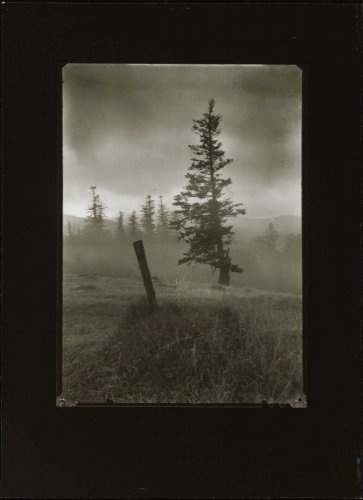

Sudek did not hide the methods of his work from friends, students and journalists, so we have a lot of evidence of how the master’s photographs were born. Here, for example, is the story of photographer Ludvik Baran about one photo walk. “(Sudek) aimed the apparatus at the chosen motive between six and seven o’clock in the evening in the summer. Janda (Rudolf Janda, famous Czech photographer - A.V.) knew the duration of Sudek's exposures, which lasted about ten minutes, so instead of waiting he went to pick blueberries. He returned half an hour later. Sudek and Peter Gelbich debated about contemporary fine art – about Fiala and Schima. Yanda listened for a while, then remembered that it was time to return. But Sudek, lying on the moss, answered: We are exhibiting. This photograph of a Silesian virgin forest (Sudek later showed it to Janda) had a soft haze light that gently washed over the roots, stumps and grasses like a magical twilight; this kind of light would be difficult to capture any other way. It was possible to create the image after more than half an hour of exposure with the old-style lens as obscured as possible. Sudek divided the exposure into several phases

and thus transformed the atmosphere of the motif into an amazing sensation of light.”

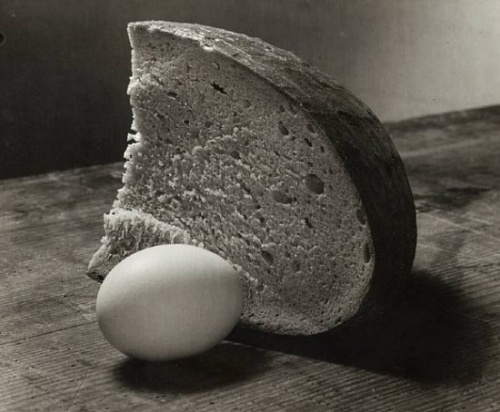

When shooting still lifes in the studio, Sudek did not measure exposure, or rather, he measured it in an unconventional way. During the exhibition he could brew and drink a glass of tea - by the way, good tea, especially jasmine tea, was his weakness. His other weakness was music - he used it when he no longer wanted tea: “Exposition - two sides of Vivaldi.” Probably Sudek is the only photographer who measured exposure by the time it took to drink a glass of tea or listen to an opera aria!

In the post-war period, in the Czech Republic, as well as throughout the world (not only in the socialist camp - just remember the notorious “witch hunt” in the USA), persecution of cultural figures began. During this difficult time, Sudek’s studio turned into a kind of “cultural oasis”; photographers, artists, writers, musicians gathered in it - musical evenings were held in the studio every Thursday. Of course, the authorities could not help but react, although no one dared to directly attack the famous photographer. Albums were still published and exhibitions were held, but they were often accompanied by harsh criticism of his photographs that “do not reflect modern realities.” Nevertheless, they did not interfere with his work - and this was more than enough for the master.

Sudek spent his entire life using antediluvian, heavy and clumsy cameras. In 1940, he saw a photograph of 30 * 40 centimeters, printed using the contact method, without enlargement. The highest quality of the print and the richness of halftones shocked the photographer, since then a 30 * 40 format camera became his main tool, although he also used others - also not small, for example, a Kodak panoramic camera with 10 * 30 centimeter negatives.

They said about Sudek: “If he’s not at a concert or filming somewhere in the city, then you’ll find him at home printing photographs.” The photographer was extremely responsible about printing, working for hours on each negative. Many researchers write that his prints were strikingly different from the negatives - but we are not talking about image manipulation in the modern sense of the word. Sudek could tweak a few subtle nuances, and the average negative would suddenly turn out to be a beautiful print. I can’t help but remember Karl Bryullov: “Art begins where it begins a little” or Henri Cartier-Bresson: “I think that there is no big difference between photographers, but small differences are very important.” However, the statement that Sudek’s photographs can only be viewed in the author’s print seems to me to be a great exaggeration - most admirers of his talent get acquainted with them on the pages of albums and magazines, or even in monographs with very questionable print quality, or - scary to say - by looking at them on the monitor screen.

And this exaggeration is not so harmless; it allows one to draw very unexpected conclusions. For example, Alexander Lapin in his book “Photography How” wrote about Sudek as a photographer who paid special attention to photographic expressiveness, by which he meant accuracy in conveying the smallest details and textures, three-dimensionality of the image, and some other characteristics achieved mainly in printing. By analogy with picturesqueness in the fine arts, he proposed calling these qualities “photographicity.” “A striking example of such photography is the work of such great masters as Ansel Adams..., as well as Joseph Sudek. Their photographs are amazing, they are real examples of photographic art, if you highlight “photographic” in the last two words. If the key word in this combination is “art” in its traditional sense, then, of course, art is unthinkable without form-creation.” Despite the abundance of pompous words (“great masters”, “their photographs are amazing”, “real examples of photographic art”) the main idea of this statement is that Joseph Sudek (like Ansel Adams) is more of a craftsman than an artist, maybe even a master printing, but not capable of form-creation.

I am not going to dispute Lapin’s statements on the merits - of course, the compositional solution of the photograph is much more important than the laboratory tricks of the printer, although they can play a decisive role (here it is worth remembering again about “a little bit” and about “small differences”). I will simply remind the reader once again of my statement that in Sudek’s photographs, print plays an important but auxiliary role, certainly not more significant than the compositional solution achieved by this very “form-creativity”.

In 1956, an illustrated book about Sudek’s work was published, which brought him financial independence. But he did not leave to “rest on his laurels”; on the contrary, he threw himself into creativity with even greater zeal: “Now there is enough money, you can start working,” he told his sister. Or maybe it's a legend? In any case, outwardly little had changed in his life; he still lived more than modestly and worked very hard. He lived for about 20 more years, during which several of the master’s photo albums were published,many exhibitions – both in our homeland and far beyond its borders. In 1961, the exhibition “Josef Sudek in Fine Art” was held in Prague, which featured more than a hundred images of the master, from pencil drawings to sculptural portraits. Sudek may be the only photographer in the world to receive such an honor.