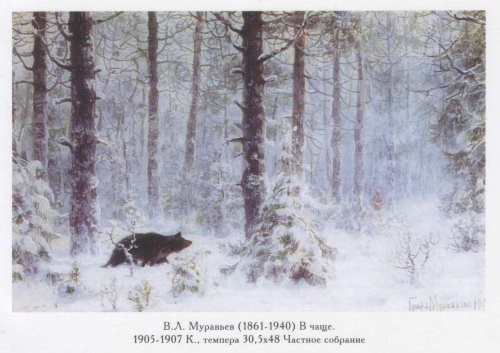

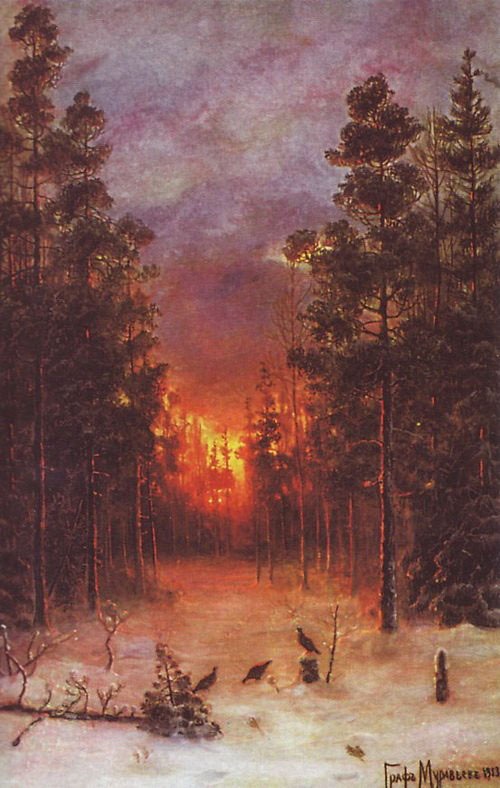

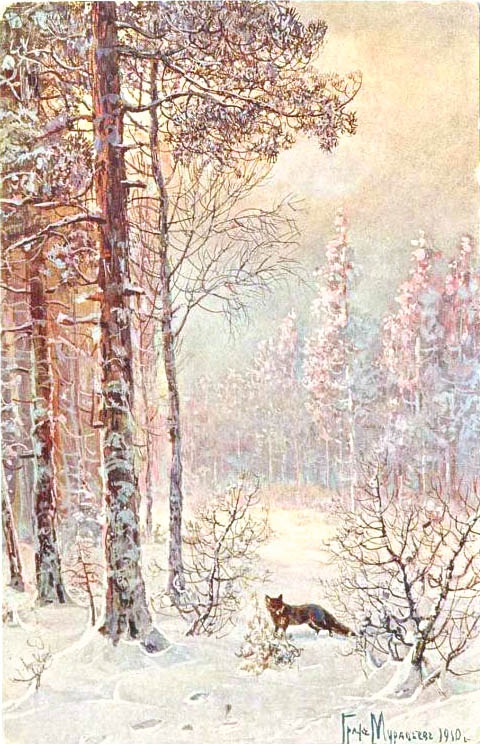

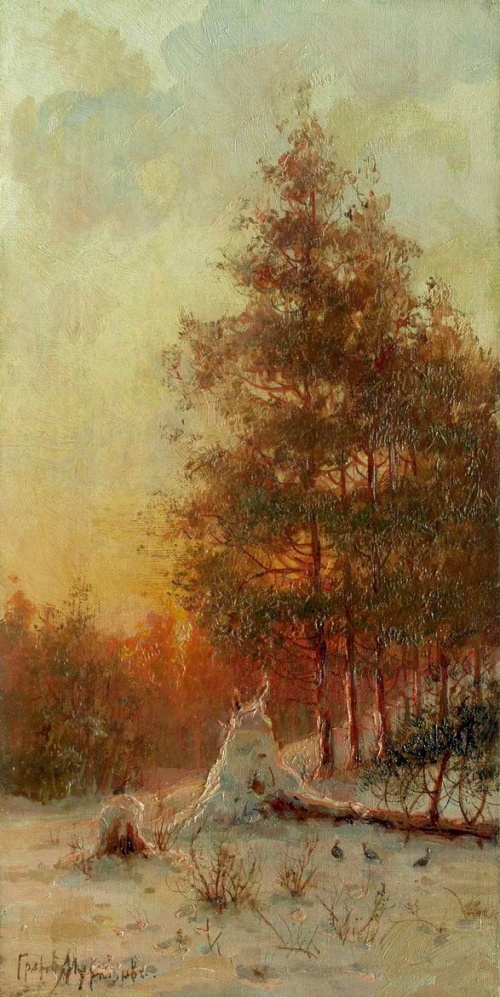

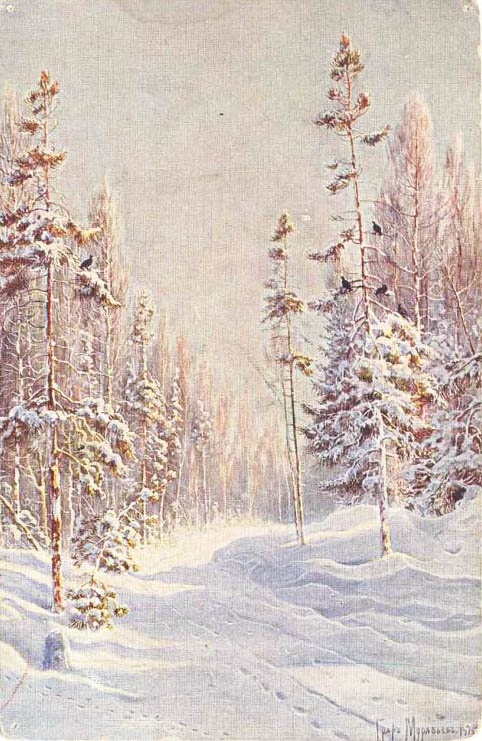

Hunting painting by Count Muravyov (80 works)

Разрешение картинок от 335x500px до 6448x4224px

Vera Fedorovna Komissarzhevskaya and Vladimir Leonidovich Muravyov:

In the history of Russian painting there are many paintings depicting hunting as a lordly pastime or a peasant craft with many hunters, guns, packs of hunting dogs and the inevitable corpses of animals. Some contemporaries liked such paintings because they evoked nostalgic memories of hunting. Others, on the contrary, were repulsed by the boundless cruelty towards living nature.

However, hunting is not only a way of obtaining food. It's also a martial art. To be a real hunter, you need to be able to listen to the forest, recognize the tracks of animals, and know their habits. The final goal is nothing compared to this combat. There is a special hunting romance hidden in tracking game. And shooting is already a harsh prose of life. The artist Vladimir Leonidovich Muravyov was precisely a romantic. Perhaps he is the only Russian artist who managed to poeticize hunting and attract the attention of the general public to it.

A nobleman, the grandson of Count M.N. Muravyov, who received his title for suppressing the uprising in Poland, Vladimir Muravyov was accustomed from childhood to denying himself nothing.

Having left the Corps of Pages in 1881, he became a volunteer student in M. K. Klodt’s landscape class at the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts. In addition, Muravyov attended sessions with the landscape painter K.Ya. Kryzhitsky, at which he willingly shared his experience with everyone.

Muravyov’s artistic education was not systematic: the position of a free student did not oblige him to anything, and Muravyov himself did not strive to improve his skills. A rake and reveler, a regular at social balls, he lived in grand style, fortunately his background and money allowed it. He did not need to think about his daily bread, so art was just entertainment for him. In 1883, while still an unknown, not fully formed artist, V. Muravyov married Vera Fedorovna Komissarzhevskaya, a future famous actress.

Muravyov's married life did not work out. He believed that his wife was an ordinary woman with a penchant for housekeeping. She wanted to take part in his development as an artist, to become his friend and assistant. She wanted to live by his interests, accompany him to sketches, give advice, but he believed that in art, as in hunting, there was no place for a woman. His wife reproached him for his addiction to entertainment, for the fact that he was not able to devote his life to art and was able to exchange creativity for cards and partying. But he stubbornly did not want to change his habits, even for the sake of his wife. It seemed that Muravyov’s savage lifestyle and wasting his fortune in restaurants contributed more to his inspiration than a happy married life. Such a marriage, based on misunderstanding, could not last long. Two years later, Muravyov cheated on his wife. His chosen one was Vera Fedorovna’s sister. This completely erased the ardent and passionate love of the aspiring artist and a brilliant, talented woman in the past. But the new marriage also broke up in 1890.

The lordly manners of Count V. Muravyov, his extreme cruelty towards both spouses led to the fact that Vera Komissarzhevskaya remembered her ex-husband only in a sharply negative tone, but the fact remains: Count Muravyov is a “notorious scoundrel” in life and an extraordinary artist pure soul in his paintings - these are the two poles of his nature. A peculiar result of an unsuccessful family life was the first painting by V. Muravyov, shown at an exhibition in 1885.

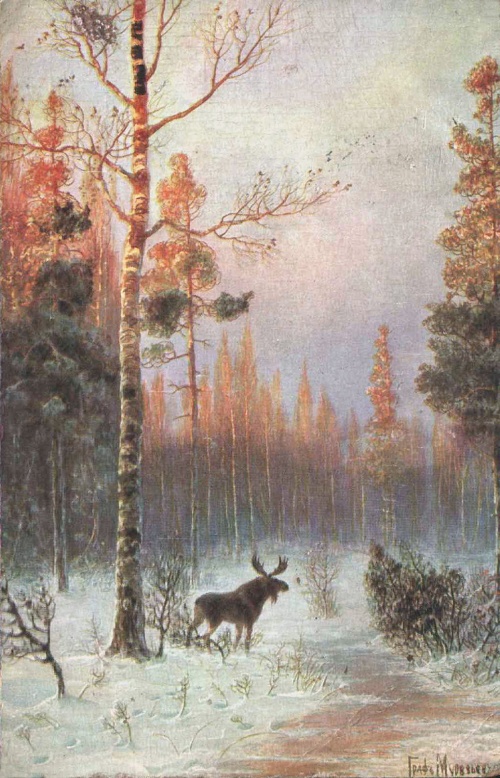

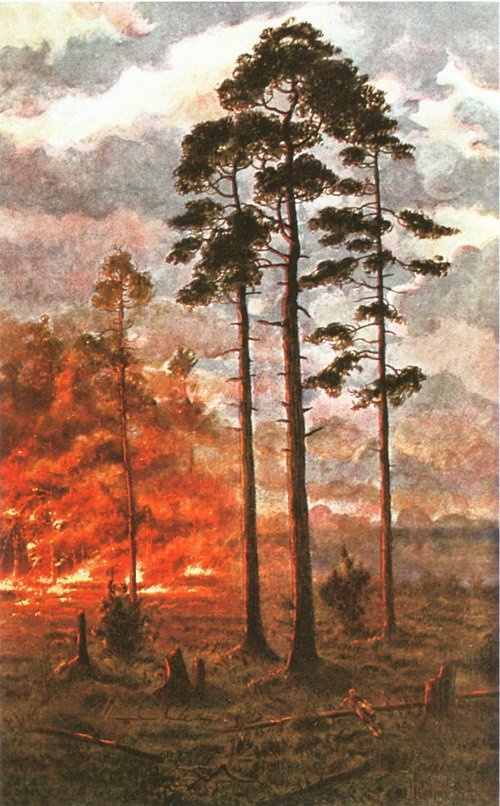

A year later, a new idol appeared in the artist’s life - Julius Yulievich Klever. Expelled from the Academy of Arts, Clover managed to achieve recognition in the circles of the St. Petersburg nobility thanks to new subjects and virtuoso techniques for performing forest sunsets and winter nature. Clover's fame was so great that Muravyov tried to imitate the maestro in everything, even in the way he worked on paintings. Thus, it is known that during a session Clover put a bottle of cognac on the table, put pickled cranberries and lingonberries on a saucer, saying: “Don’t get drunk, but a small sip of good wine invigorates.” And in Muravyov’s workshop there was always a glass, a bottle of wine and a sandwich on a special table. From time to time he went to the table, took a few sips for inspiration and picked up his brush again. Clover could paint a whole picture in the presence of the customer. Muravyov strove for the same professionalism, and no everyday adversity could stop him. Clover endlessly replicated the favorite motif of a bright sunset in the winter wilderness. And in Muravyov’s paintings there are still the same blazing sunsets. The circle of admirers of Klever and Muravyov was approximately the same - their paintings were bought mainly by members of the royal family and their associates.

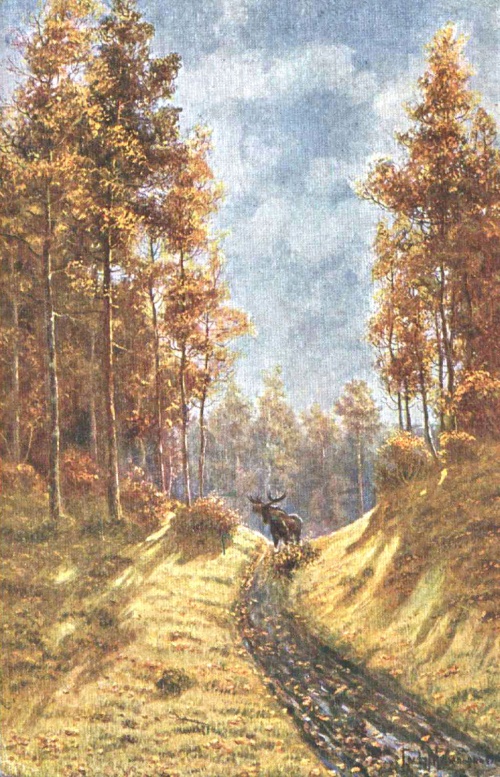

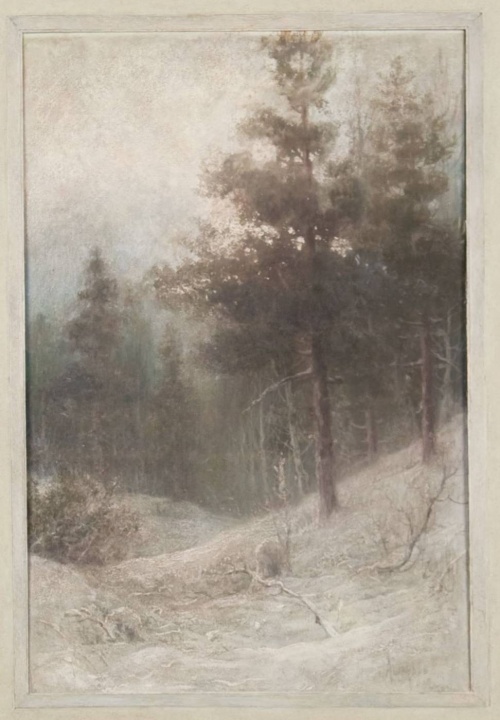

Muravyov's art knew neither ups nor downs. He was outside of fashion and artistic trends: like Clover, he always painted in the studio, often from memory or fantasizing during a session. The fashionable passion for plein air did not affect him. The compositions of his paintings are usually deliberately scenic, which was in keeping with the academic tradition. The plots did not differ in variety: scenes illustrating hunting and the habits of animals were often complemented by spectacular romantic sunsets and sunrises, and less often - moonlight. Occasionally, the artist was interested in the changing states of nature, such as the onset of a thunderstorm.

Muravyov's landscapes were usually intended for viewers experienced in hunting. All the nuances of each type of hunting are almost impossible to depict in one picture, so the artist ignored individual moments and focused on the poetic side of the topic, believing that hunting connoisseurs would easily remember their real impressions. Indeed, how, for example, can one illustrate the draft of woodcocks? The male woodcock has been known to fly above the trees before dawn and begin to “tug,” or make a call. The female, who is on the ground, answers him, after which the male rushes towards her. You can only shoot a flying Samoa. But all these nuances are not present in Muravyov’s painting. His “Woodcock Pulling” is a poetic landscape with birch trees, a swamp and the shine of the sun in the wild.

Or how to depict the hunt for wood grouse in painting? It is known that when capercaillie display, they do not hear anything around them. And only in these moments, no more than three to five seconds, can you approach the capercaillie lek. The search for wood grouse can take quite a long time, and only endless patience can achieve results. Seeing a singing capercaillie is the dream of any hunter. Having looked at pre-revolutionary postcards - reproductions from the artist's paintings - and understood the basics of hunting, you involuntarily become charged with the romance of hunting, which you had never even imagined before.

Sometimes a shooting hunter did end up on the canvases of Vladimir Muravyov, but the main place was given not to him, but to his unfortunate victims. Thus, one can involuntarily sympathize with the unenviable fate of the hare, who jumped out right under the barrel of the hunter’s gun, or with the black grouse, to which he managed to get so close that in the next moment he would certainly shoot at them.

But such “cruel” hunting scenes from Muravyov are the exception rather than the rule. For him, the anticipation of a hunting trophy, admiring the life of animals and even, to some extent, empathy for them are more important. With undisguised delight, Muravyov again and again depicted a grouse current.

However, unlike Clover, Muravyov did not strive for artistic titles and awards. In his mind, the title of count outweighed all other possible honors that existed in Russia at that time for the artist. With constant consistency, he signed his paintings: “Count Muravyov.” Over time, he developed his own pictorial style: first he painted in oils, and by the beginning of the 20th century he switched to mixed media, often using gouache. His paintings are easily recognizable due to their subjects, as well as their unique texture. The trunks and branches of trees were often scratched with a pen or highlighted in relief with paint. A broad stroke was used to depict snow-covered meadows. This combination determined the naturalness of the impression, thanks to which even today old postcards, from which the artist’s work is mainly known, look good and enjoy constant success among philocartists.

On the other hand, many postcards reproducing Muravyov’s paintings are objectively quite rare and highly valued. This is explained by the fact that most of them were published before the First World War in Lodz (published by A. Ostrovsky) and in Nuremberg (published by TSN). With the outbreak of hostilities, the connection between these cities and Russia ceased and some postcards probably never made it to Russia.

Muravyov was considered self-taught. The circle of admirers of his art was too narrow; he was too far from contemporary landscape painting and from the vigorous exhibition activity. His art seemed to be intended for a select few; he was practically unknown to critics. He created his own world of artistic images, and there were not many such artists in Russia. But his entrepreneurial spirit was limited to bohemian life. It was Clover who could prepare public opinion, invite journalists to his exhibitions and almost dictate laudatory articles about his paintings to leading newspapers. Muravyov was not able to constantly attract the public. Perhaps that is why his work was relatively rarely covered in the press.

It is interesting that after the revolution of 1917, Muravyov’s life and work did not end. He did not emigrate abroad, like many other contemporary Russian artists. He was not carried away by socialist realism either. He lived, painted his favorite grouse and capercaillie currents, and signed himself simply “Muravyov,” although his art of the Soviet era is much less known than the pre-revolutionary one. The hard times of the Civil War brought him to Rostov-on-Don. The count's origin did not in the least interfere with the artist's arrangement in his new life: Muravyov presented himself as a descendant of the famous Decembrist.

But in the conditions of building a socialist society, the artist felt more and more useless every year. There were no more rich customers, and workers and peasants needed symbols of a bright future. Among his fellow painters, known before the revolution and who stood under the banner of the new art, Muravyov had no friends or acquaintances who could, on occasion, intercede for the “singer of the hunt” before the revolutionary authorities. Who knows, maybe his simple hunting landscapes might have appealed to Soviet leaders, who were known to love hunting.

He wrote less and less and was forced to sell his elegant “hunts” at bargain prices at the Rostov bazaar. Forgotten by everyone, he died in 1940.

One can persistently deny an artist the professionalism characteristic of real artists, and call the animals from his paintings frozen sculptures. You can endlessly accuse Muravyov of a dissolute lifestyle and completely justify his wives. One can endlessly emphasize the fact that Muravyov was never awarded artistic titles. The only thing that remains an immutable truth is that Muravyov’s paintings are always filled with an enthusiastic feeling of sincere love for his native nature. Perhaps this is why postcards with reproductions of his paintings are a constant success among philocartists.