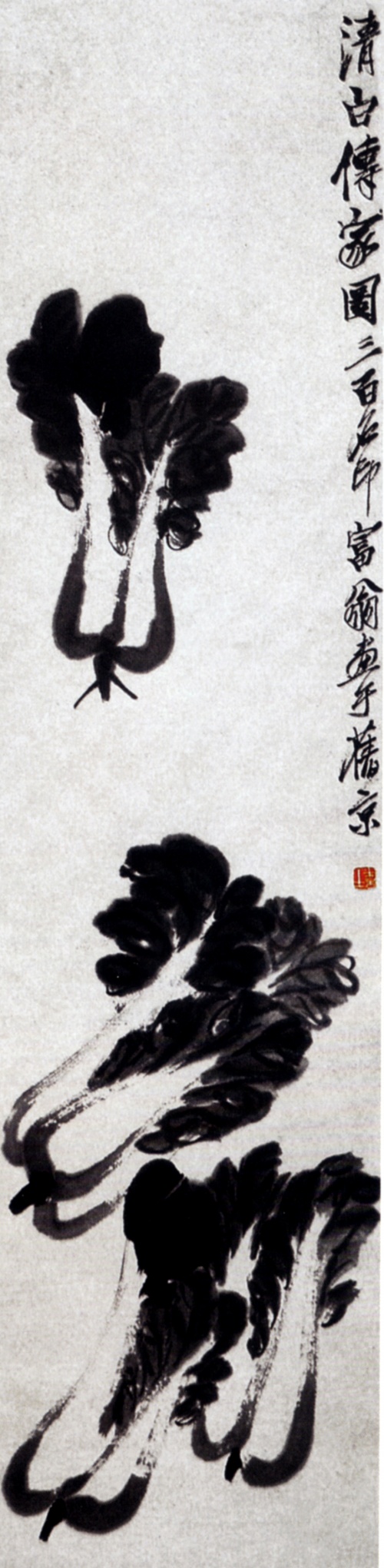

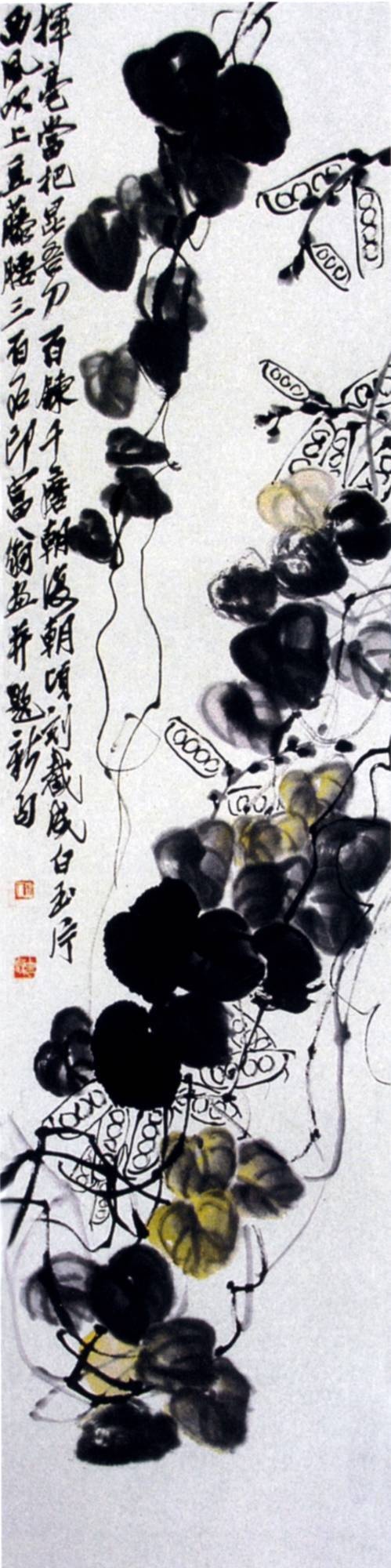

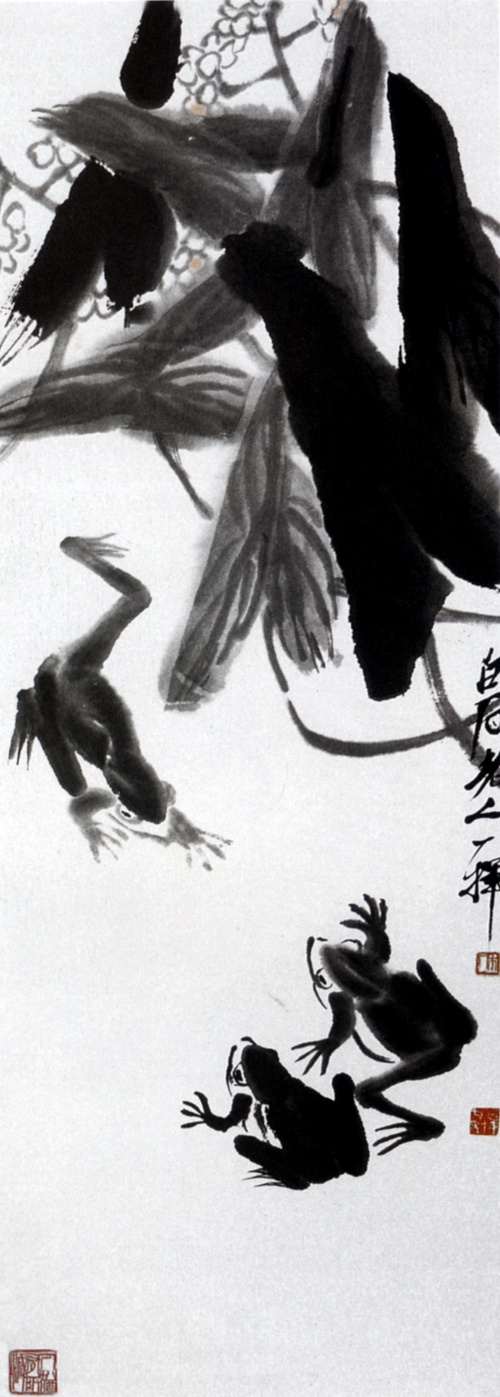

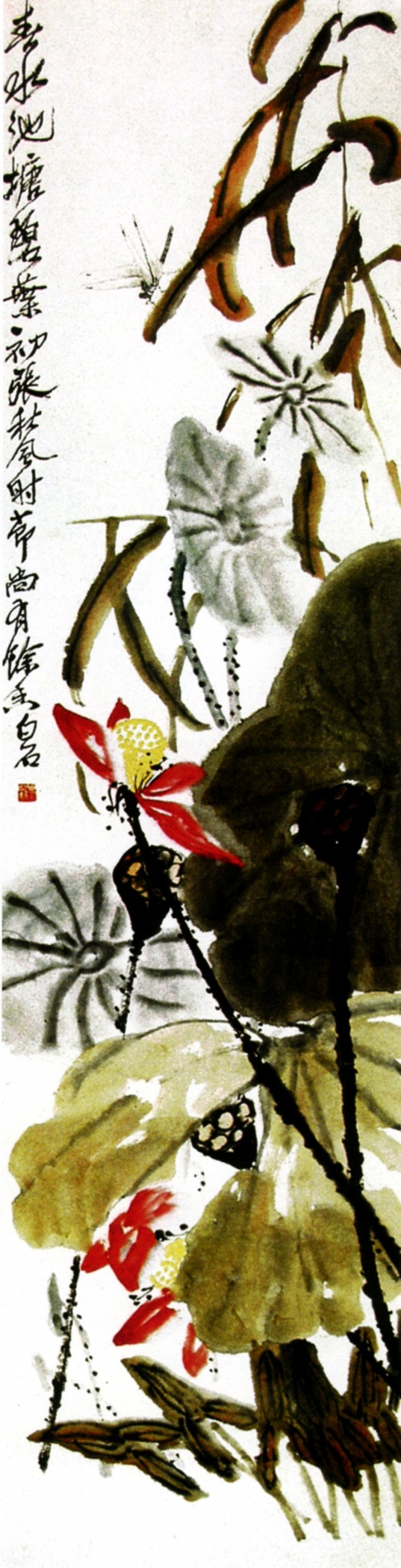

Qi Bai-shi (1860-1957) - Chinese painter (222 works)

Разрешение картинок от 400x340px до 2623x3825px

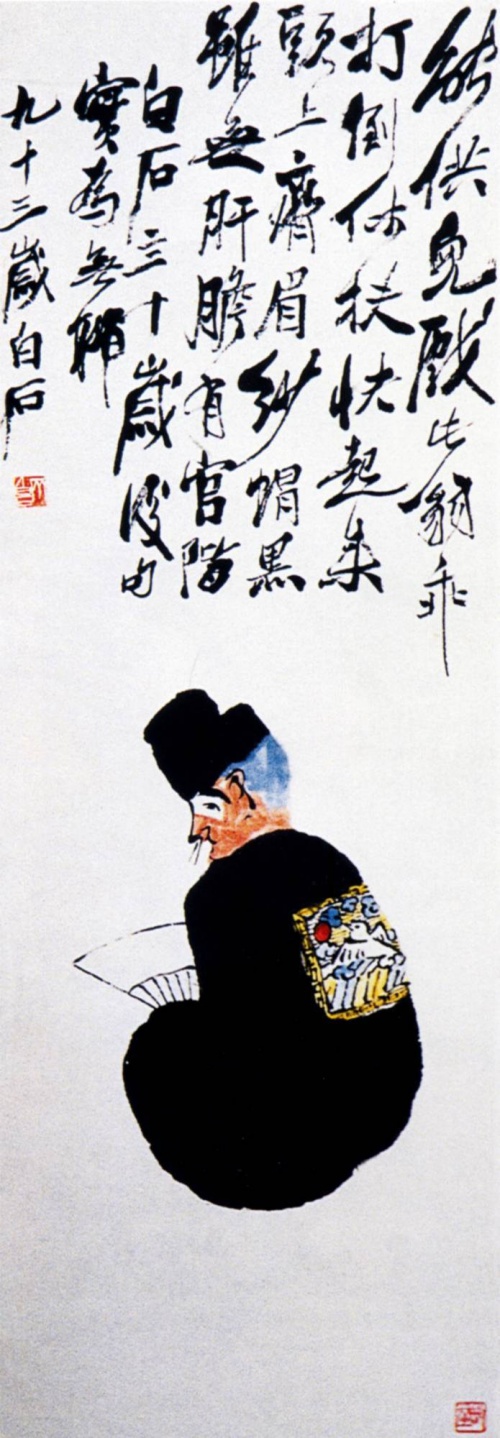

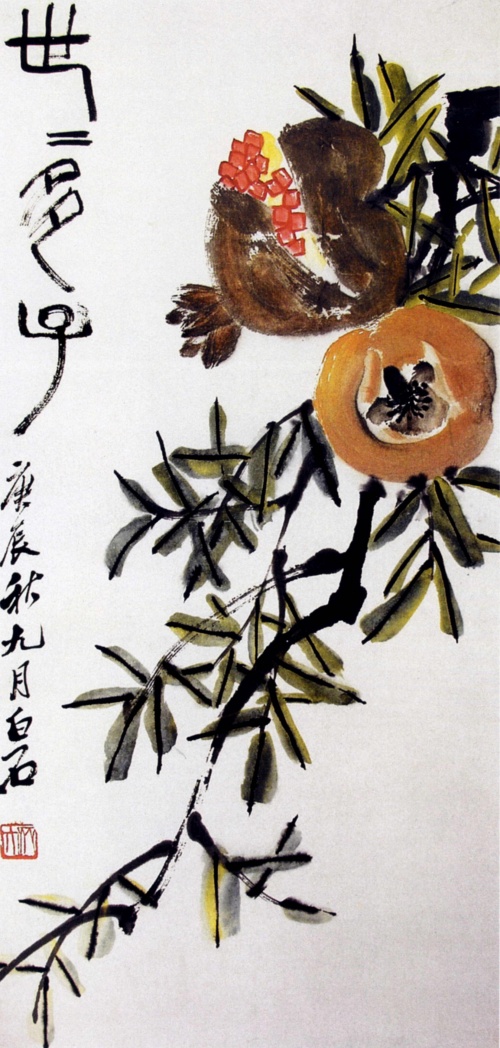

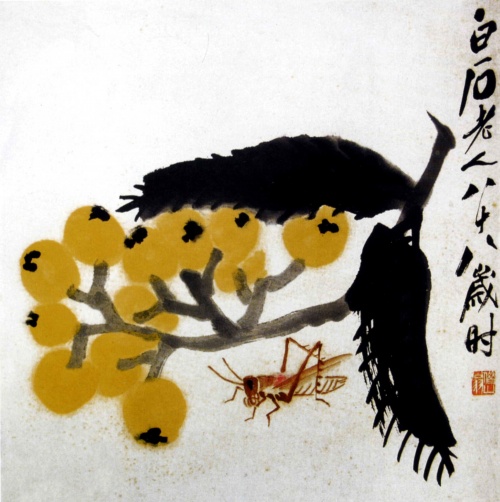

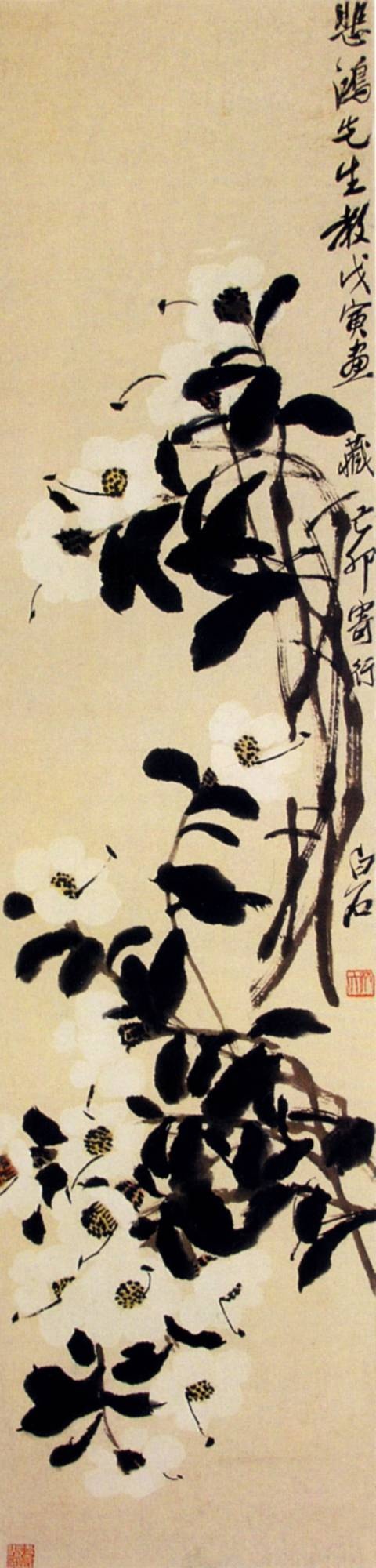

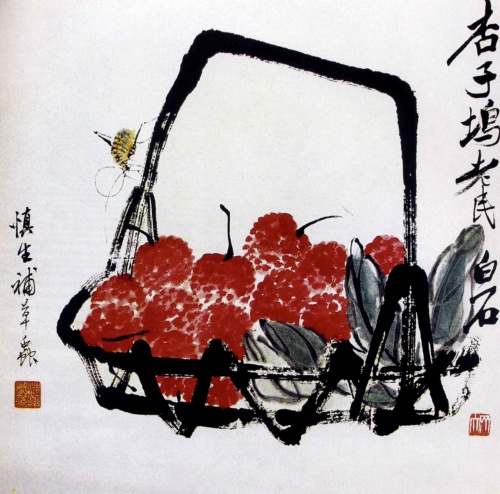

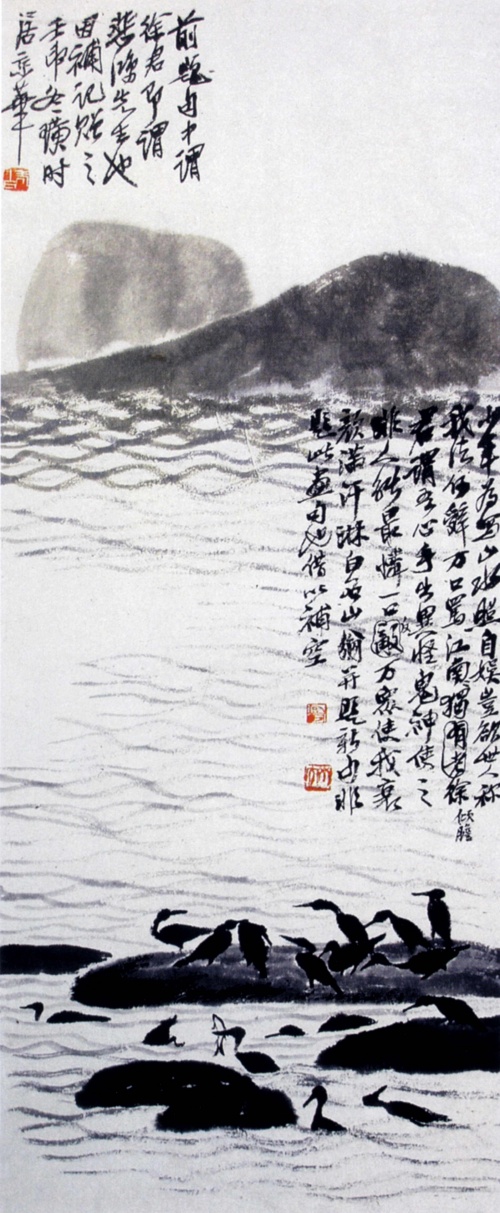

Qi Bai-shi (1860-1957) - Chinese painter. The intensity of the creative work of the great Chinese artist Qi Baishi is compared to Van Gogh. Over ten years of serious painting, Van Gogh created more than 800 paintings and even more drawings. Qi Baishi, who worked for more than seventy years, left people several thousand of his works. He was not only an amazingly subtle artist, able to convey all the richness of tonal transitions, but also a philosopher, poet, and mentor. When drawing, he likened himself to plants and believed that only the meihua plum could fully understand him. The artist, in his words, “bathes in orchid water and washes his hair with the aroma of flowers.”

Qi Bai-shi was born on November 22, 1860 into a very poor Chinese family. Grandfather and father collected firewood for sale to feed their children. Xiangtan County, where the future artist was born, was unusually picturesque.

It was this county, its green valleys and lakes surrounded by low mountains, that Qi Baishi sang in his poetry and paintings. His grandfather was an original and talented artist, whom his fellow countrymen called the Straight Soul, because he always openly expressed his opinion and spoke out against injustice. My mother was just as determined. But my father, on the contrary, most often simply quietly swallowed his tears. Qi Baishi was born prematurely, and his mother had to sacrifice a lot to raise him healthy and strong. Qi Baishi's first teacher was his grandfather, who began teaching him to write his name with a stick when he was not even three years old. In elementary school, where Qi Baishi went to study at the age of eight, he read an anthology of classical poetry, Qian Jia Shi (Poems of a Thousand Poets), lines from which he remembered even in his old age.

Qi Baishi began copying traditional images of the thunder god Yu-gong, which were placed above the cribs of newborns to scare away evil spirits, and tried to make drawings. At the age of twelve, Qi Baishi, according to tradition, was married to a girl from the Chen family, whose name was Chun Jun. Since the boy was not good at peasant work, his father apprenticed him to a carpenter, and then, at his own request, to a woodcarver. It was here that Qi Baishi understood how craft and art differ from each other.

In the house of one of his acquaintances, Qi Baishi once saw several volumes of a five-color edition of the encyclopedia “Jiezi yuan huazhuan” (“Tale of Painting from the Mustard Seed Garden”), which appeared in the 17th century. They shocked the young man so much that he began to carefully copy the drawings placed there.

In 1889, Qi Baishi's drawings were seen by the painter, poet and calligrapher Qin Yuan, who invited him to study further.

Already at the age of seventy, Qi Baishi wrote the following poetic lines about this time:

In my poor village I started studying very late.

And I didn’t study seriously until I was 27 years old.

There was a real problem - there was not even oil for the lamps.

I lit a pine torch and read poems by Tang poets.

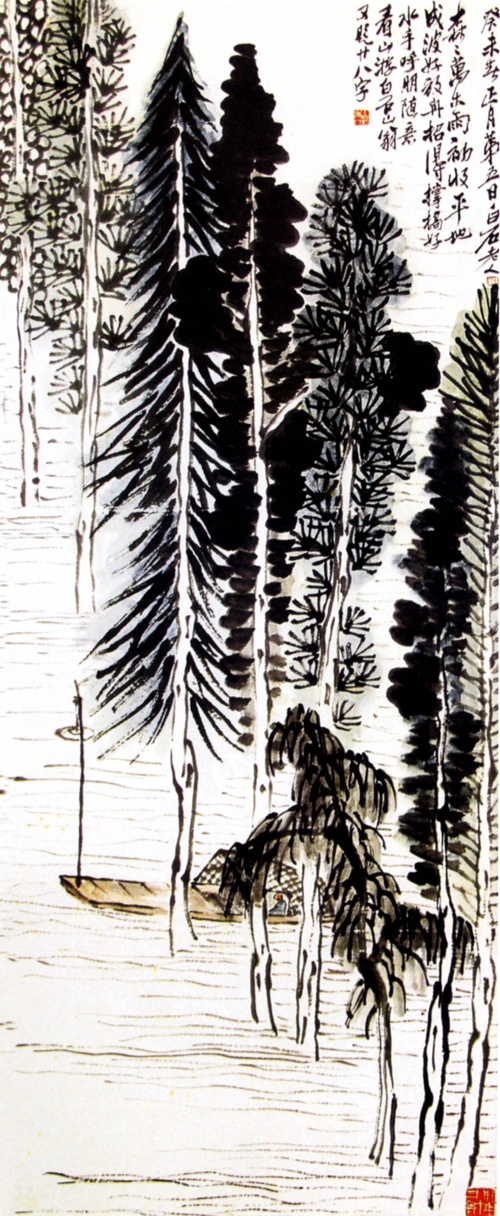

Qi Baishi began to paint paintings to order. He especially loved to depict landscapes, as well as scenes with “flowers and birds” traditional in Chinese art. Later, images of historical events and historical heroes began to appear. Qi Baishi loved to be among scholars and poets at the Drakensberg Hill Poetry Society and the Horse Poetry Society.

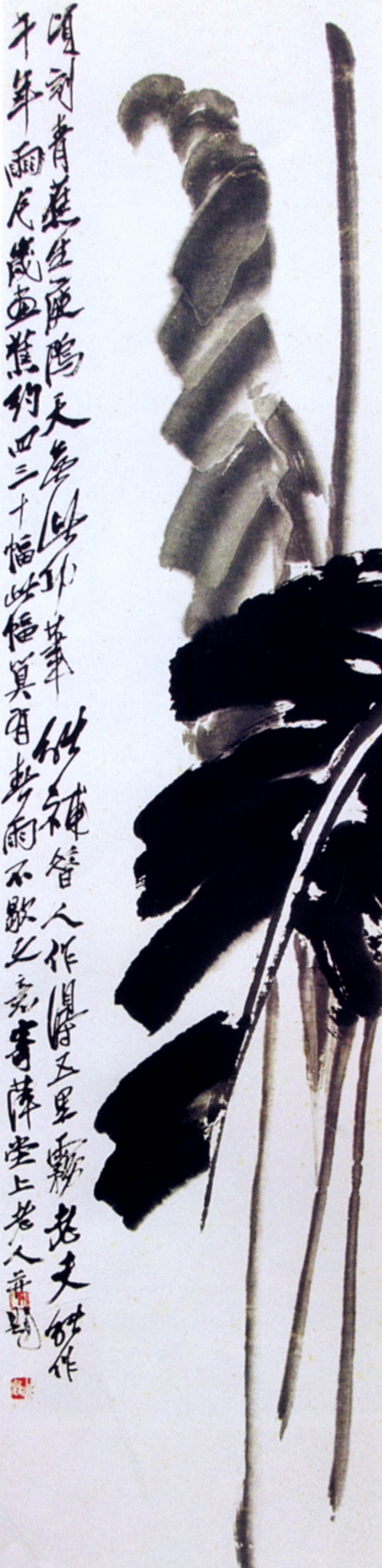

In 1894, Qi Baishi began to seriously study calligraphy, then became interested in carving seals. And by creating twelve landscape scrolls with views of Mount Hengshan and selling them, Qi Baishi was able to build a small studio house in the town of Meikun, where he was delighted by the blooming meihua plums. Qi Baishi called his workshop “The Cabinet of a Thousand Plums” or “The Cabinet of Poetry.” The bananas he had planted grew near the house, and his favorite water lilies floated in the pond.

In 1902, Qi Baishi was invited to the large cultural center of Xi'an to study painting with the daughter of a rich man. The turning point in his life was traveling to Beijing, and then to other historical places. He was lucky enough to get acquainted with many rare books. As a result, the style of his painting and calligraphy changed, and he began to carve seals in a new way.

Gradually, Qi Baishi began to introduce, as he himself put it, “beauty” into his works. In 1910, the artist created 52 landscape scrolls with views of Mount Jie.

In 1917, the master again visited Beijing, where he met the famous master of “flowers and birds” Chen Shizeng, who was delighted with the seals carved by Qi Baishi. In 1919, at almost sixty years of age, the artist finally moved with his family to Beijing and began painting with special zeal. All his life he knew how to find teachers whose creativity appealed to him and corresponded to his inner nature. And, as he himself admitted, he always remained a student.

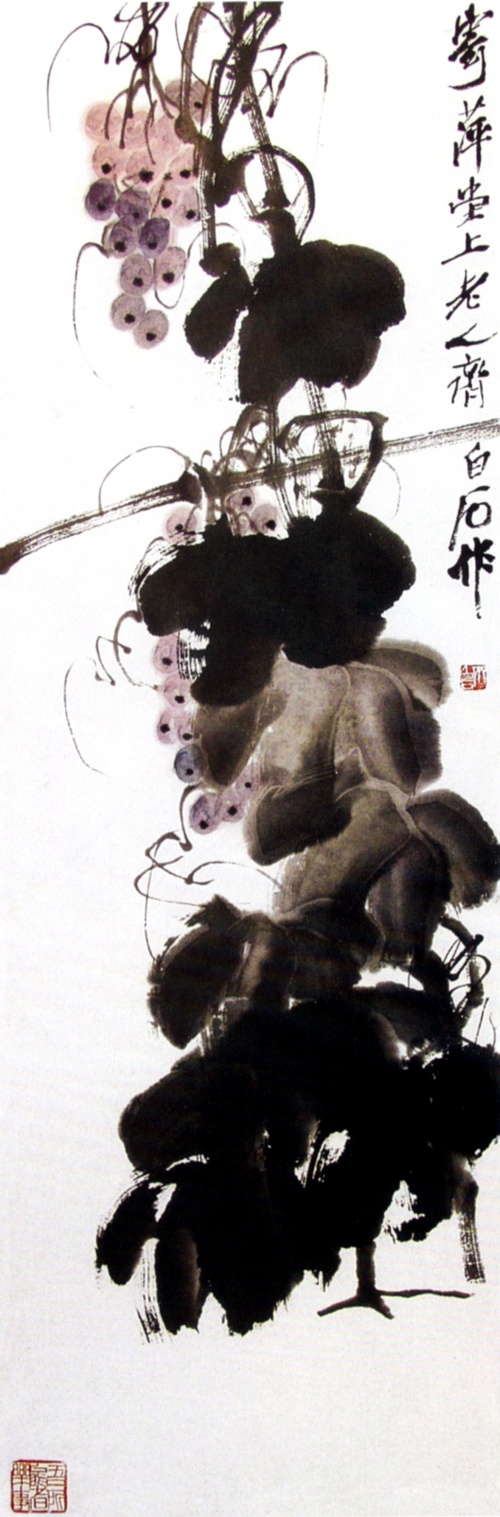

For example, when copying the scrolls of Ni Yunlin and Shen Zhou, Qi Baishi did not use any halftones and did not achieve the illusion of an enveloping soft haze. He seemed to be translating the image into his contemporary language. What was round and soft in Qi Baishi’s paintings was made angular, more expressive, and clear. Having studied the style

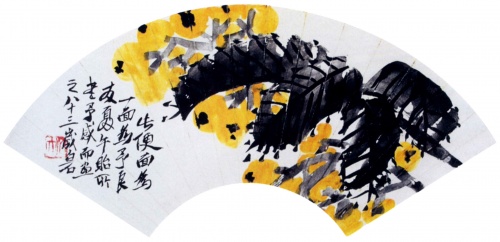

ь Zhu Yes, Qi Baishi began to use his “red flowers, black leaves” technique.

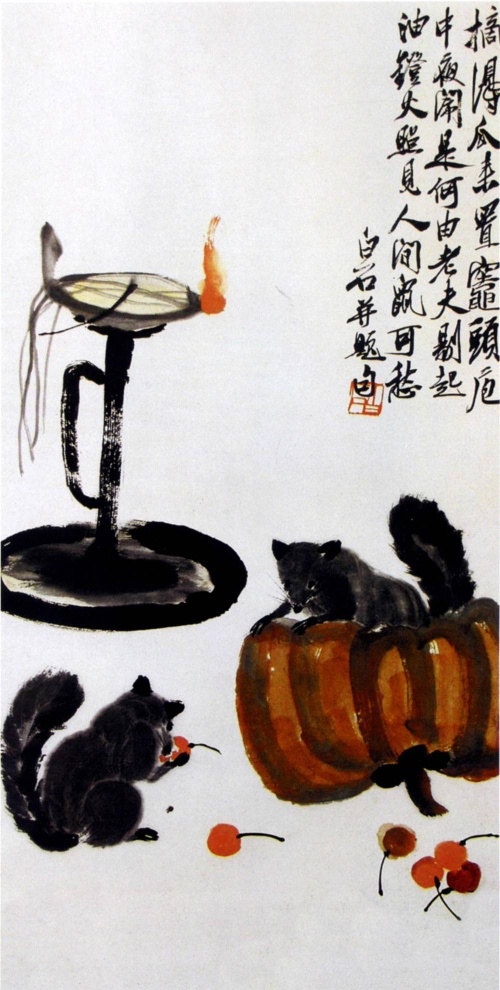

In Beijing, Qi Baishi met many artists, poets, and actors. In the 1920s, his works were exhibited in Japan and then in Paris. And Qi Baishi himself became seriously interested in Chan Buddhism. Walking around Beijing, he loved to wander through the beautiful parks and gardens. One of the best shrimp scrolls, for example, was written in the garden of a certain Zhang. From Beijing, Qi Baishi traveled to his native place in connection with the death of his mother, and then visited Sichuan. Throughout his life, the artist did not break ties with folk traditions. He knew how to see in something small - a blade of grass, a flower, a butterfly or a shrimp, the whole cosmos, the endless and enticing universe.

The Japanese occupation, the death of his grandson and closest friend set Qi Baishi in a very gloomy mood. At the same time, Qi Baishi officially married for the second time - to Bao Chu, who died in 1943, although she was only forty-two years old.

When the Japanese captured Beijing, Qi Baishi tried by all means to ensure that his paintings were not used for their own purposes, and even hung a note on the door of his workshop: “Old Baishi has a bad heart and is unable to receive guests.”

In the 30-40s, Qi Baishi actively opposed vulgar naturalism, wrote scrolls that were perceived as satire on traitors to the motherland, those who served the interventionists. The inscriptions on the scrolls tell those who look at them how to understand this or that metaphor. On one scroll it was written: “I have two hands to improve my skill, but it is very difficult to scratch exactly where it itches.”

Only in 1946, when the Japanese were expelled, Qi Baishi returned to teach at the Academy of Fine Arts, and in 1947 he became its head.

In the latest works of Qi Baishi, the harmony and balance of form is striking. Butterflies and plants, the most diverse states of nature, Qi Baishi conveyed with the help of lines and color spots.

In the 50s, when Qi Baishi gained worldwide recognition, he created his best works not only in the field of painting, but also calligraphy, and formulated in poetic lines his opinions about creativity as a philosophical category and about the basis on which he himself is engaged in creativity.

When you look at the works created by Qi Baishi in the 40s - “Pastel of Rice and Locusts”, “Squirrel and Cherries”, “Meihua Flowers”, “Fly on a Platter”, “Grasshopper”, “Chicks Enjoying the Sun”, or in the fifties - “Fruits of Lichzhi”, “Chrysanthemum”, “Palm Tree”, etc., you understand with particular poignancy that poetry is everything that surrounds us.

Qi Baishi died on September 16, 1957. He managed to convey to his descendants his great delight, admiration, and the image of the world he had discovered.

Bogdanov P.S., Bogdanova G.B.