Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) (63 works) (1 part)

Разрешение картинок от 2023x3044px до 8814x6181px

Katsushika Hokusai (Japanese: 葛飾 北斎; 1760, Edo (now Tokyo) - May 10, 1849, ibid.) - Japanese ukiyo-e artist, illustrator, engraver. He worked under many pseudonyms. He is one of the most famous Japanese engravers in the West.

The beginning of the way

Born, as many believe, in the Waragesui quarter of the Honjo district in Edo (modern Tokyo). His real name is Tokitaro, but throughout his creative life he took many different pseudonyms.

At the age of 18, Hokusai entered the studio of Katsukawa Shunsho (1726–1792), a famous ukiyo-e artist famous for his portraits of kabuki actors. In 1779, the young artist made a series of quite confidently composed theatrical portraits.

In 1791, Hokusai was invited to make several engravings for the publisher Tsutaya Juzaburo. After Shunsho's death in 1792, the Katsukawa school was taken over by another of Shunsho's students, Katsukawa Shunei (1762–1819), and Hokusai apparently stopped painting portraits of actors.

Own style. Surimono

1793 and 1794 were turning points in Hokusai's career. The artist refused to pander to the tastes of the public of that time, which demanded the usual works in the ukiyo-e genre, and began to develop his own style, drawing on some techniques from the Japanese schools of painting Rimpa and Tosa, as well as applying the European perspective.

In 1795, his illustrations for the poetic anthology “Keka Edo Murasaki” were published. Between 1796 and 1799, Hokusai painted many single prints and album sheets. The latest “surimono”, as these custom prints were called, were a huge success. As a result, other artists immediately began to imitate them.

Just in 1796, the artist began to use the pseudonym Hokusai, which later became widely known. With this name, starting from 1798, he signed engraving sheets and paintings, he signed some commissioned illustrations with the pseudonym Tatsumasa, illustrations for commercial novels were published under the name Tokitaro, other large-scale prints and illustrations for books were signed Kako or Sorobek. In 1800, at the age of 41, the artist began to call himself Gakejin Hokusai - “Mad Hokusai of Painting.”

Public performance

From about this time, although he lived somewhat removed from society, Hokusai, having gained a certain authority, often demonstrated his art in public. In 1804, on the territory of the Edo Temple, the artist painted an image of Bodhidharma measuring 240 m². Between 1804 and 1813 he illustrated comic stories, the so-called. “yomihon”, famous authors Kyokutei Bakin and Ryutei Tanehiko.

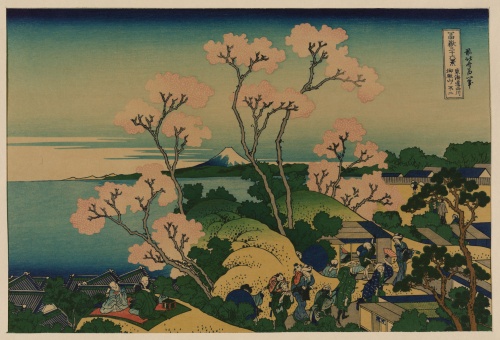

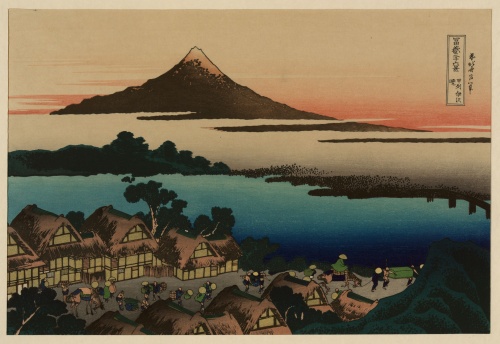

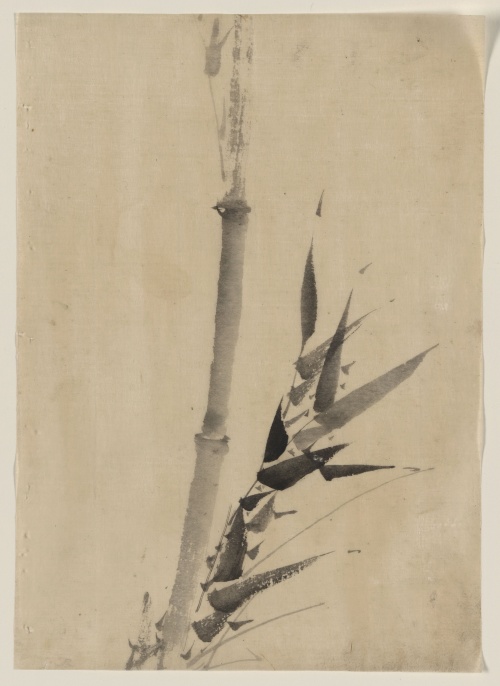

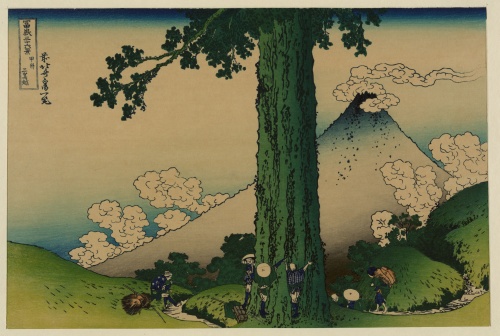

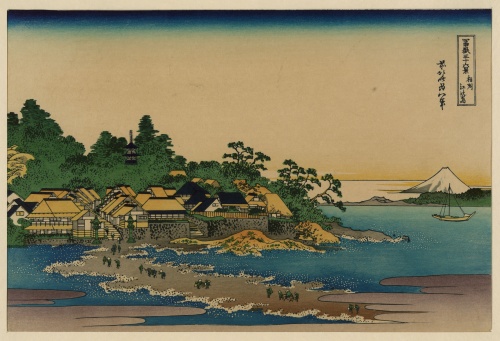

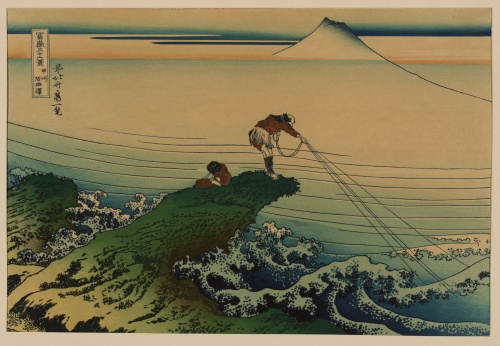

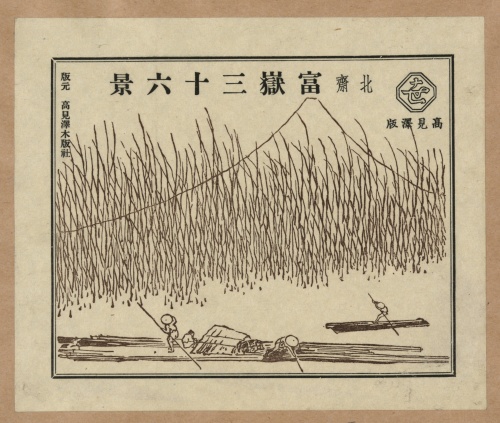

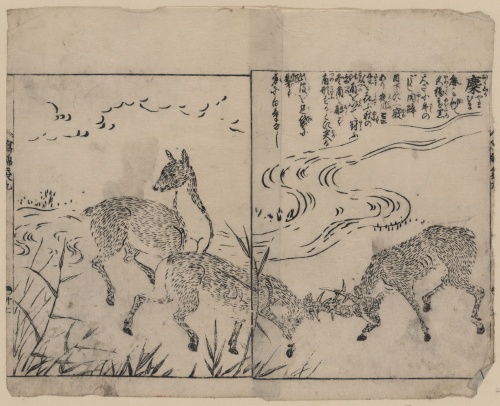

Albums and series. Solitary life in Miura

In 1812, his close friendship with the artist Bokusen (1775-1824) began, as a result of which, between 1814 and 1834, a series of illustrated albums “Hokusai Manga” (“Drawings of Hokusai”) was published in the city of Nagoya. The famous series of landscape prints “Fugaku Sanjurokkei” (“36 views of Mount Fuji”) began to appear in 1831, and in the early 1830s. Hokusai produced prints of famous waterfalls, bridges, birds and ghosts, i.e. those works for which he is best known in our time. At the end of 1834, just before the publication of his series Fugaku Hyakkei (100 Views of Mount Fuji), a masterpiece of his book engravings, the artist left Edo and lived for a year in a working-class area near Uraga on the Miura Peninsula south of Edo. At the same time (in 1835), his last, serious series of engravings began to be published, “Hyakunin isshu uba ga etoki” - “One Hundred Poems as Narrated by a Nanny” (Illustrations for the collection “100 Poems of 100 Poets”). In total for this series the artist completed 28 engravings and 62 ink sketches. The publication of a series of woodcuts for the poetic anthology “Hyakunin Isshu” was interrupted after the publication of 28 sheets; the series remained unfinished.

Back to Edo. Poverty

In 1836, the artist returned to Edo when the city was destroyed by the surrounding poor, and he had to earn a living by selling his own paintings. In 1839, a fire broke out in Hokusai's workshop, destroying all the sketches and working materials. After this, Hokusai apparently painted very little, and produced virtually no prints or book illustrations. The most famous of his students was probably Totoya Hockey (1780-1850), who illustrated books and surimono.

Wikipedia

***

Katsushika Hokusai is one of the most widely known Japanese artists, who became famous mainly in the art of graphics, but also left a rich legacy in painting, drawing, and book illustration. He was a writer and poet, constantly interested in the scientific achievements of his time, and was a tireless traveler.

But the most important thing is that Hokusai was an artist-philosopher, and everything that was revealed to his penetrating gaze and recorded on paper with his brush was interpreted by him from the point of view of the universal laws of the universe, eternal and constantly changing life. He was interested in the diversity of phenomena, their internal relationships, and their subordination to general laws. He not only tried to capture what he saw, but constantly reflected on what he saw, be it scenes of city life, which he sketched with lyrical

th, then from a grotesque point of view, or nature with its changing seasons, weather, lighting. Everything was part of living life for him.

In Japanese art of the late 17th and early 18th centuries, two main trends were clearly identified. One was aimed at preserving the old, centuries-old traditions that developed during the period of dominance of the feudal class. The other, which arose at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, was associated with the emergence on the historical stage of a new urban class, which gradually developed its own forms of culture that met their needs and ideals. Deprived of political and social privileges, the urban class directed its energy into the sphere of culture, partly using the traditions of the feudal period, but also creating fundamentally new forms of it: Kabuki theater imbued with the folk spirit, stories with scenes from urban life, tercet poetry - haiku, wood engraving - ukiyo-e.

Hokusai came from a family of artisans in Edo (modern Tokyo), was fond of drawing as a child, and from the age of thirteen began to study the art of engraving. His stay in the studio of the famous artist Katsukawa Syunse, where he stayed from 1778 to 1795, had a particularly great influence on his creative destiny.

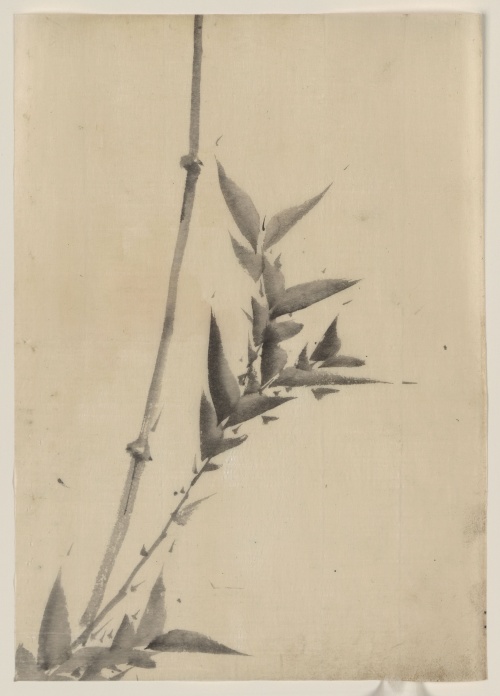

Engraving became Hokusai's most fruitful field of activity. A large period of his work after leaving the Syunse workshop (around 1797 to 1810) was devoted to working on a special type of prints - surimono, published in the form of greeting cards, often with good wishes - figures of the gods of happiness and wealth, plants and animals that evoked the same associations . However, Hokusai soon went beyond traditional subjects and began to depict scenes from city life, often accompanying them with poetic, humorous and witty inscriptions, as well as flowers, birds, and insects. Working in the small space of a surimono postcard, Hokusai achieved precision in composition, color relationships, and the beauty of specific simple things and their combinations.

In 1814, Hokusai published the first book of his multi-volume work Manga, intended as a manual for artists. Over the years, he published 15 volumes of Manga, which contained drawings with a wide variety of subjects - from landscapes and sketches of natural motifs to scenes from city life, faces of people with a variety of expressions, figures of wrestlers and dancers, characters from historical chronicles, myths and legends.

It is not surprising that the precision of poses and movements, often conveyed by only one expressive line, amazed European artists when they first saw these albums by Hokusai in the mid-19th century.

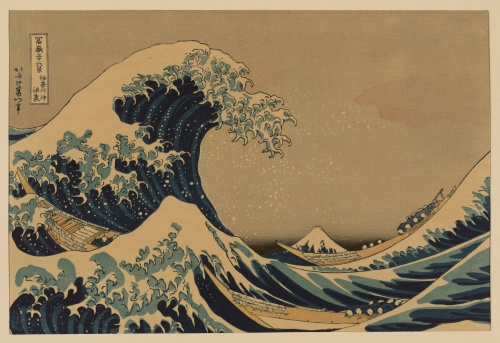

The twenties and thirties of the 19th century were the heyday of Hokusai’s work, when he created a series of large easel prints as a result of long trips around the country. These are "Views of remarkable bridges of various provinces" (1827-1830), "Journey to the waterfalls of various provinces" (1827-1833), "Poets of China and Japan" (1830), "Thirty-six views of Fuji" (1823-1829), " One Hundred Views of Fuji" (1834-1835). Having visited all parts of the country, Hokusai discovered a new beauty of Japan, which other artists seemed to have not noticed before him, although the landscape genre in engraving was not his discovery. It is known that landscape series were created by Hiroshige, Kunisada, Kuniyoshi and other masters.

However, in his landscapes, as in Manga’s drawings, Hokusai refused to divide motifs into those worthy of attention and those unworthy, or those that were beautiful and ugly. Everything in nature seemed beautiful to him - a majestic mountain range, and a snail on a yellowed leaf.

If in the landscapes executed by the masters of monochrome painting of Suibokuga, the main thoughts were about the universe, about the essence of Nature-Cosmos, then in the works of Hokusai depicting specific places and their features - mountain gorges and waterfalls in certain provinces, sea bays, wooded hillsides - reflected the view of a simple person who perceived nature as the natural environment of his life. It is not for nothing that Hokusai’s landscapes from the series “Thirty-Six Views of Fuji,” considered one of the master’s masterpieces, are populated by people going about their daily business: coopers and log sawyers, fishermen and travelers with heavy luggage. Here landscape and genre are fused, forming a unity where man is commensurate with nature. It is in this organic unity of man with the natural world that the artist’s high philosophical thought is contained. Here it receives especially great significance and even symbolic meaning by the silhouette of Mount Fuji repeated on each sheet of the engraving. This mountain, as a sacred symbol of the country and at the same time as an ideal image of beauty, was depicted by many artists before Hokusai and his contemporaries.

For Hokusai, this is also a national shrine, and that is why he wanted to show it from different places and from different points of view, at different times of the year: now barely visible behind the island of Tsukuba, now observed at sunset at the Ryogoku Bridge by travelers at the crossing, now as if popping up among the raging waves of the ocean. Only one sheet of this series, called by the master “Victory Wind. Clear Day (Red Fuji),” is deprived

human presence, and the mountain appears in all its unique beauty and symbolic significance. This image became central to the series, a generalized expression of the artist’s worldview, his understanding of the tasks of art and beauty as an expression of truth, which has been a national feature of Japanese culture for centuries.

Hokusai's innovation lies not only in the fact that he mastered some techniques of European art that became famous in Japan. His artistic discovery lies in a new look at the world and the place of man in it with the entire sphere of his feelings and his creative activity. Hokusai saw life as a single process where everything is interconnected - nature, man and everything created by him. In this he was ahead of his time, opening up still unknown ways of development of Japanese art.

Nadezhda Vinogradova

One day, two men appeared on the threshold of Hokusai’s house. One is the artist Shiba Kokan, the other is the captain of a Dutch ship who wanted to take “a piece of Japan” home. Hokusai was busy, painting while squatting with a brush with a very long handle. Each stroke made his body squirm, the artist’s muscles bulged, as if he were performing the most difficult gymnastic exercises. A few minutes - and from the spots of the spreading carcass, plants, animals, birds, people appeared from a variety of angles. The students removed the completed sheets and quickly added new ones. No alterations! The Dutchman was amazed by the action, which combined theater and mystical inspiration. The most amazing thing is that these were just sketches that Hokusai performed hundreds of exercises for!

During a short respite, the master came out to the guests and brought out several scrolls of surimoto - greeting cards. The overseas guest looked at the works with interest and listened to the artist’s explanations. This is the god of fun, Hotei, and here is admiring the moon, against the background of which a grasshopper drinks persimmon juice. The picture, like all surimotos, was accompanied by a poem composed by the master:

The moonlight is clear,

We drink wine in the fall

Glass by glass.

And this grasshopper

persimmon juice will suck,

But will he be drunk?