Mikhail Shemyakin. Part 1. Illustrations (30 works)

Разрешение картинок от 800x408px до 800x800px

In 1981, Shemyakin moved to America and since then has not sat still, traveling around the world in connection with numerous orders, exhibitions and theatrical productions. Often, it is even difficult to say in which country and in which city he spends most of his time. The master, not without irony, notes in a number of his interviews that most often he has to live on an airplane.

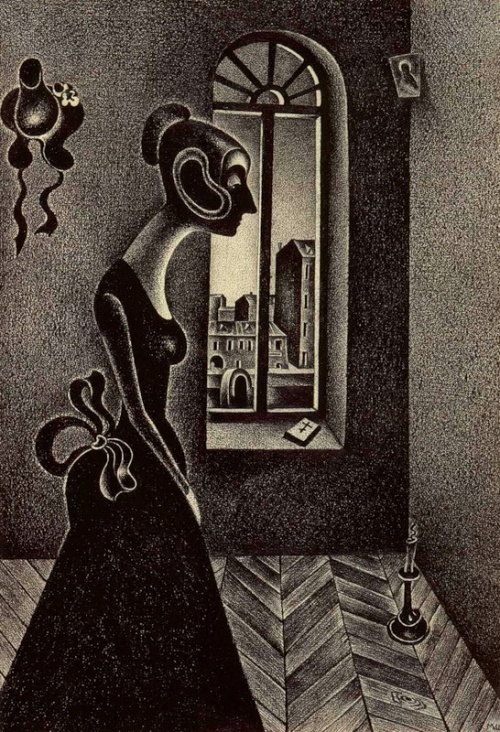

While studying at school at the Academy of Arts, M. Shemyakin prepared himself for the difficult craft of a sculptor, although his sketches even then amazed teachers with their originality, foreshadowing the emergence of a major painter with a subtle sense of coloristic harmonies. However, fate denied him the opportunity to continue his education. After forced “treatment” in a psychiatric hospital, where he was placed for his religious beliefs and then forbidden interest in avant-garde art, all paths for the aspiring artist were closed. Once free, Shemyakin wandered around the Caucasus for some time and collected instructive experience of communicating with hermits, holy fools and homeless eccentrics. Upon returning to St. Petersburg, he got a job as a rigger in the Hermitage. Contemplating the world's masterpieces every day, copying paintings close in spirit, the future master, deprived of the opportunity to continue his formal professional education, graduated from his “Academy of Arts” in the museum. Due to participation in an exhibition of works by “auxiliary workers”, organized for the 200th anniversary of the Hermitage (1964) and closed by the authorities on the third day, Shemyakin lost his last source of meager livelihood. However, he passed the test. Difficulties that could have broken a weaker soul did him good. It was during these years that Shemyakin developed as a master with his original grotesque vision of the world. Lack of funds prevented him from taking up sculpture; Then, in search of an outlet for creative energy, he turned to painting and graphics. The latter, which did not require large expenses - a pencil and paper was enough - became for him the main means of realizing the fantasies of his metaphysically oriented imagination. Shemyakin developed a special drawing technique based on the finest light-and-shadow transitions. Shemyakin created a bizarre world of images, unaffected by the destructive influences of communal life. He demonstrated one of the main features of his creative makeup: an innate sense of beauty, completely independent of external influences, ideologies, demands of fashion and the art market.

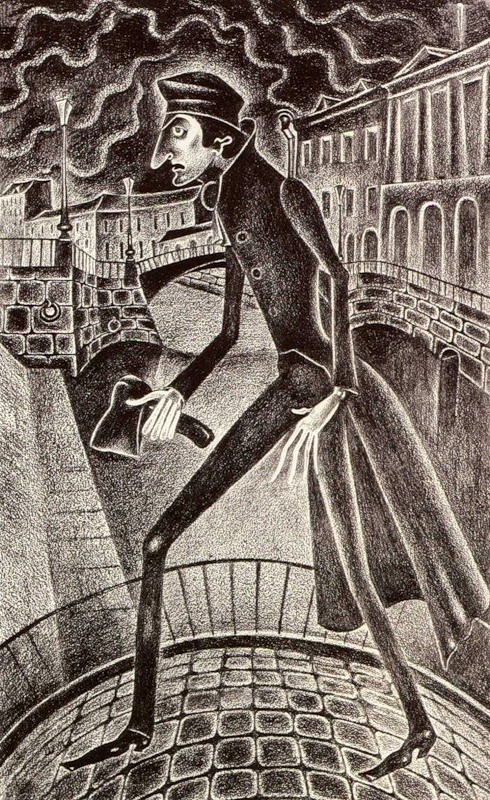

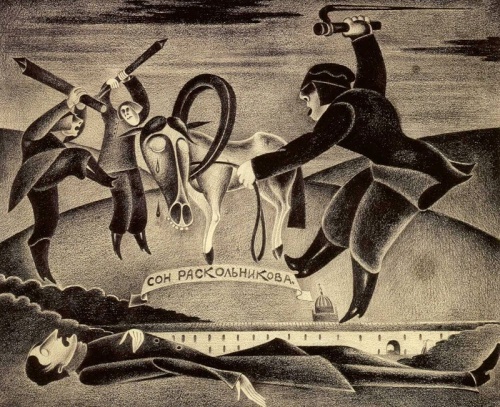

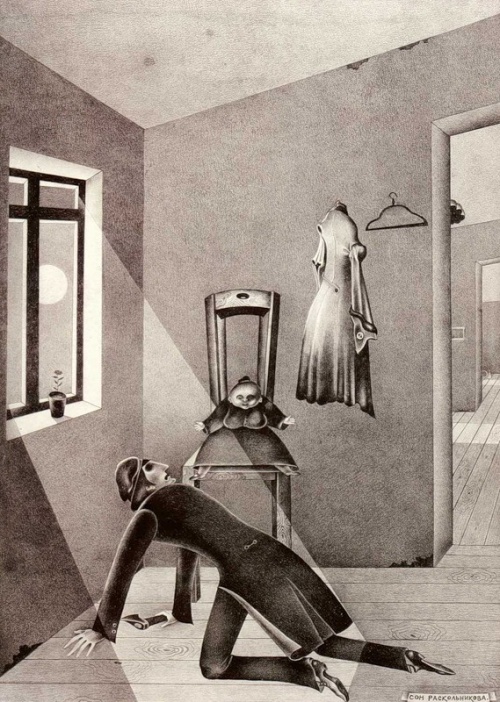

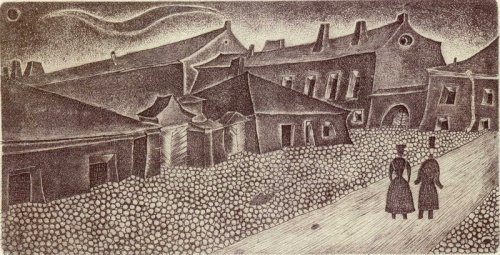

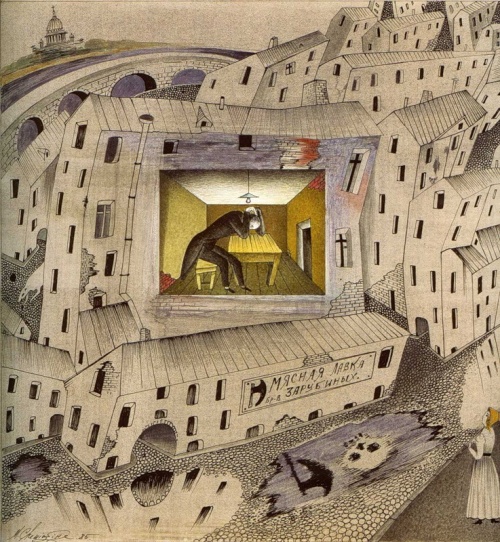

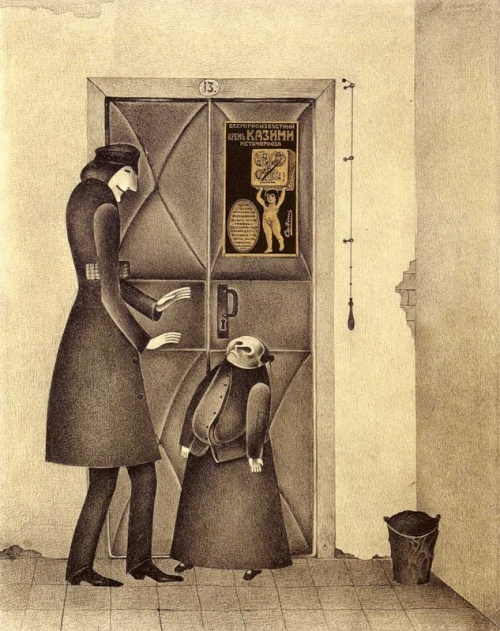

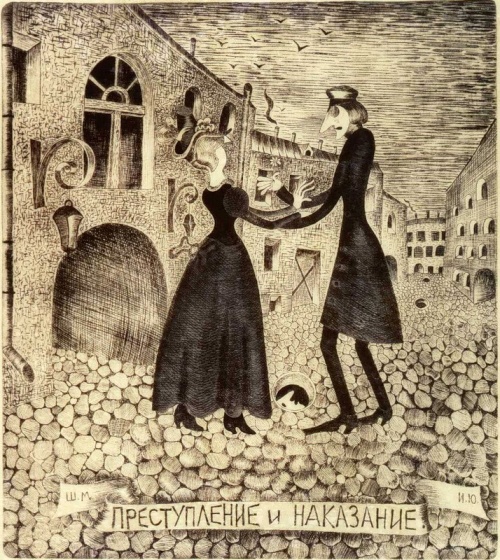

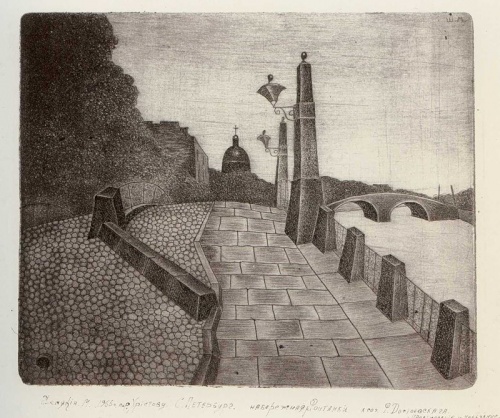

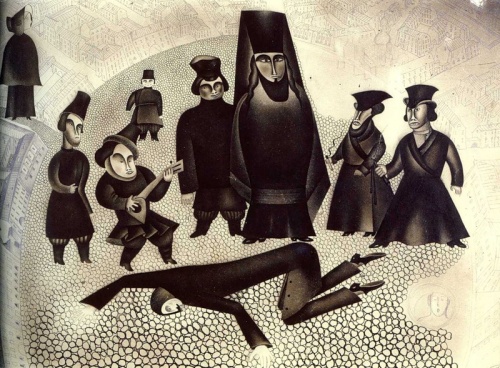

While artists usually illustrate certain works commissioned by publishing houses, Mikhail Shemyakin was guided in his choice of subjects exclusively by internal impulses and motives. Since his school years, he has had a need to make visible the images of like-minded writers. In this sense, his “illustrative” series are largely autobiographical in nature, reflecting significant moments of his own creative development. They are projections of a “magic theater” whose actors objectify the world rising from the depths of the artist’s subconscious. The autobiographical nature of the drawings clearly emerges in a series of illustrations for “Crime and Punishment”, made from 1964 to 1969. Shemyakin saw the main events of the novel primarily in Raskolnikov’s dreams and visions, which pose the hero with the problem of “crossing the threshold.” Having accumulated experience in resisting alien influences, the master felt deeply related to Dostoevsky’s idea that the “new” can enter life only as a result of the removal of the “old”, when the boundaries drawn by one or another tradition are boldly crossed. In the conditions of the 1960s, the avant-garde artist inevitably found himself in the eyes of those in power as a criminal violator of ideological laws, who could be imprisoned in a psychiatric hospital, expelled from the city and even from the country.

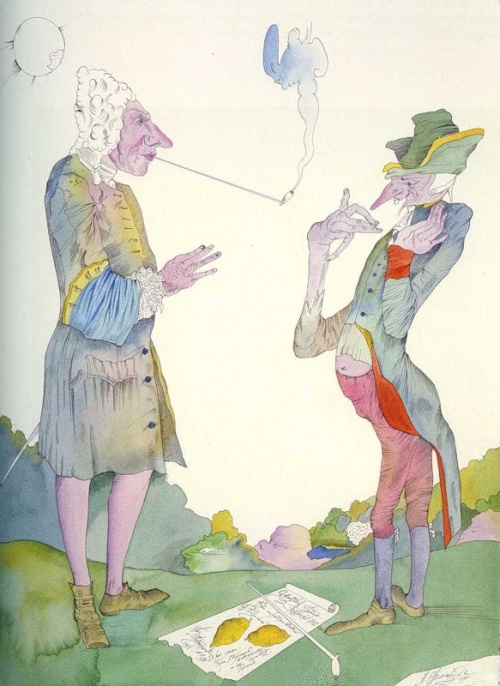

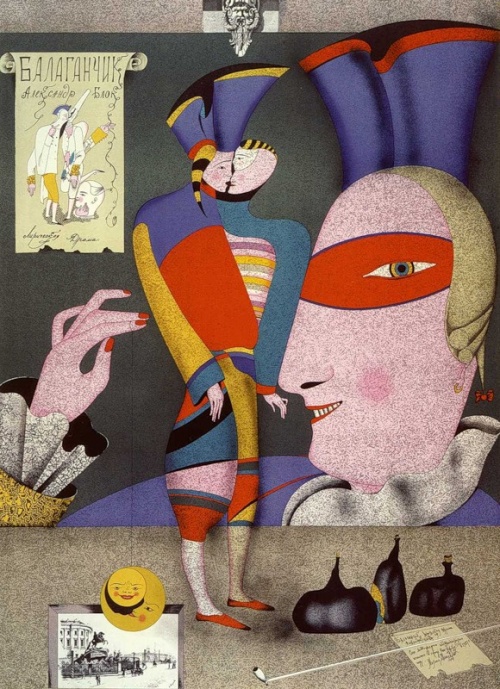

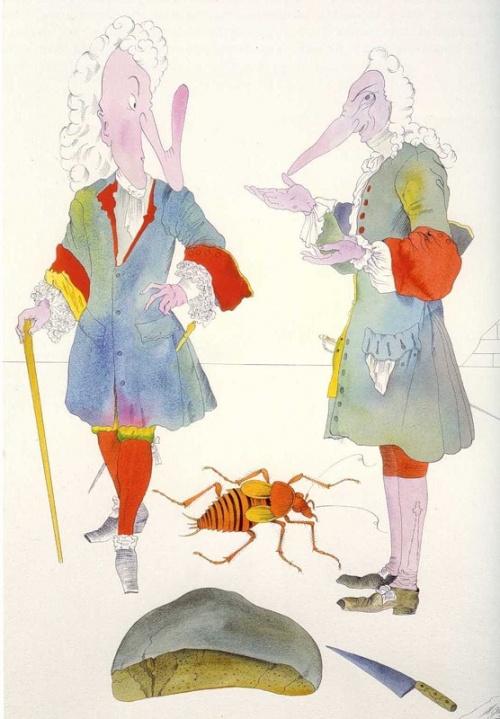

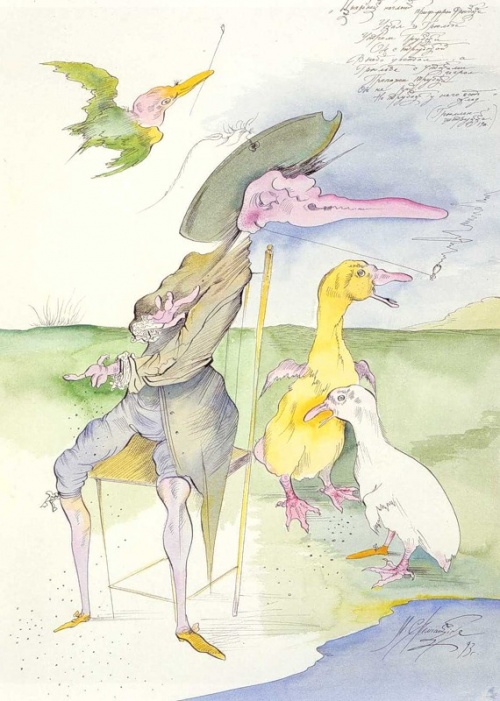

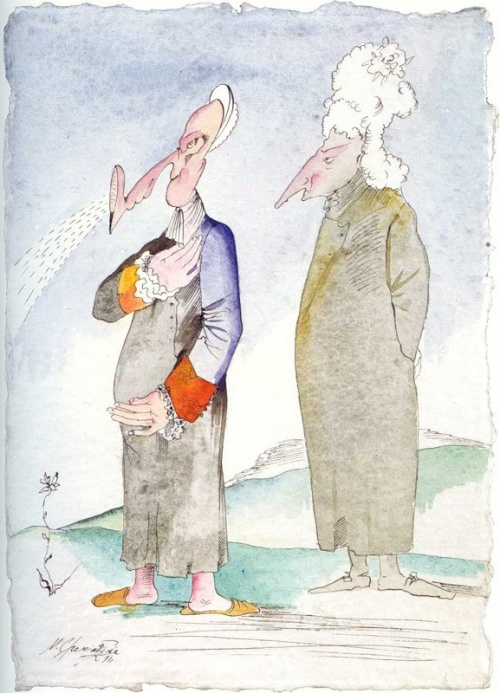

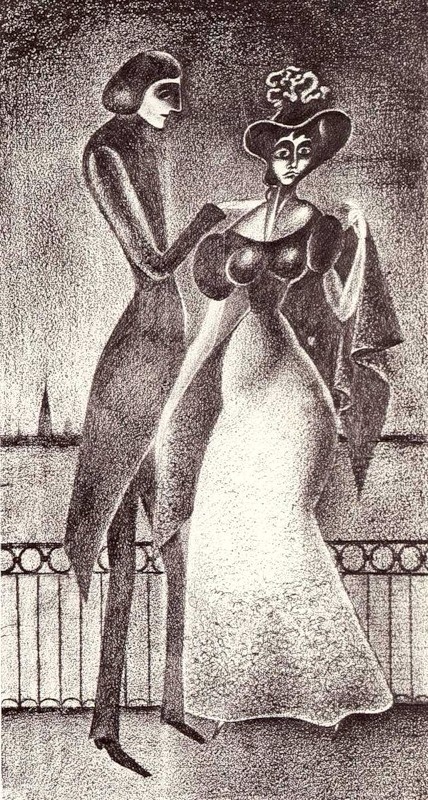

Almost simultaneously, Shemyakin became interested in the so-called “gallant scenes”. He unexpectedly showed a love for the refined culture of the 18th century with its masquerades, pastorals, and heightened eroticism. Because of this, Shemyakin subsequently began to be classified as a belated “World of Art” student. However, if the artists of the “World of Art” were overwhelmed by nostalgia for a vanished world, not without a touch of sentimentality, then Shemyakin rather parodies the style of the 18th century, turning “gallant scenes” into eerie grotesques. The characters in the paintings and hand-colored engravings of this series most closely resemble soulless dolls. Life appears as a puppet show, led by the invisible hand of a demon. With all this, one should not exaggerate the importance of the literary plot element in these works. Much more important here for the master are the complex color harmonies in the spirit of Watteau, the masterly interweaving of lines, the play of forms, colored with irony, which is the dominant mood of his worldview.

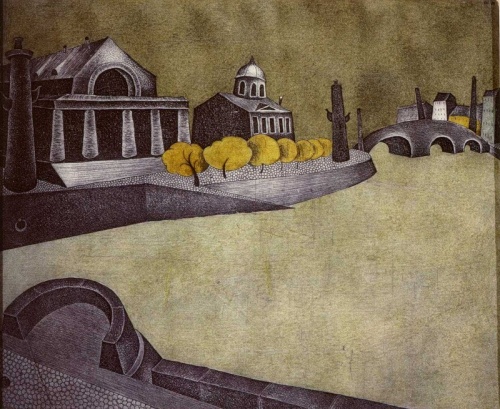

Shemyakin has been working on this theme “Carnival of St. Petersburg” - in various techniques and formats: from multi-meter paintings to small engravings - for almost three decades. “Carnivals” turned over time into an “encyclopedia” of grotesques, based on a deep understanding of the mysteries ofhuman nature in its diverse distortions, perversions and grimaces.